The goal of a natural resource damage assessment (NRDA) is restoration. While there are many steps that federal, state, and tribal agencies, collectively known as the “trustees,” take to arrive at restoration implementation, NRDA is a restoration focused process. In the first part of an NRDA, known as the assessment phase, the trustees describe adverse effects, or injuries, to natural resources and their services caused by the release of oil or a hazardous substance. Restoration discussions among the trustees start during the assessment phase because ultimately, the restoration projects that are implemented as a result of an NRDA settlement will address those injuries identified in the assessment phase.

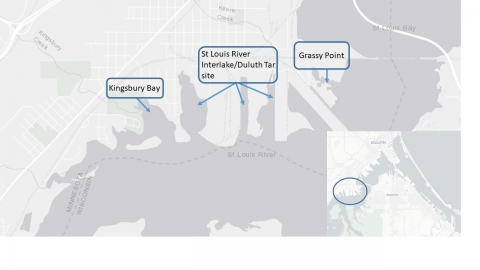

The St. Louis River/Interlake/Duluth Tar site was used for a variety of industrial purposes — including coking plants, tar and chemical companies, the production of pig iron, meat-packing, and as a rail to truck transfer point for bulk commodities — starting near the turn of the 19th century. In 1983, the St. Louis River Superfund site was added to the National Priorities List.

In November of last year, a settlement was reached between the trustees for the site and the parties responsible for the contamination. The settlement includes funds for the following restoration projects:

• Kingsbury Bay, $5,500,000, to enhance and restore a 70-acre shallow, sheltered embayment habitat that will add recreational fishing access areas and a boat launch, improve habitat, and reduce invasive vegetation.

• Kingsbury Creek watershed, $637,500, to reduce sediment deposition, improve water quality, and sustain the shallow sheltered embayment habitat of the restored Kingsbury Bay.

• Wild rice restoration, $332,000, to enhance wild rice stands within the estuary. Efforts typically include removing invasive vegetation and establishing a seed bank to provide a long-term seed source.

• Cultural education opportunities, $30,000, to develop informational displays adjacent to wild rice restoration locations to communicate the importance of wild rice to the health of the St. Louis River estuary and the cultural traditions of local Native Americans.

As is typical in NRDA, some of the restoration projects that are part of this settlement were conceptually developed by programs and groups outside of the NRDA process. The Kingsbury Bay and wild rice restoration projects were initially identified and scoped by federal, state, and tribal programs through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

Coordination with the St. Louis River AOC

The Area of Concern (AOC) program was implemented in 1987 to address the locations around the Great Lakes that were identified under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement as areas that had experienced significant environmental degradation. Each area has a number of beneficial use impairments (BUIs), which are defined as changes in the chemical, physical, or biological integrity of the Great Lakes system sufficient to cause impairments. Examples of BUIs are restrictions on fish and wildlife consumption, fish tumors or deformities, and degradation of benthos.

The St. Louis River was named one of the 31 AOCs on the U.S. side of the Great Lakes. In an effort to provide structure and ensure successful restoration of an area, each area must develop a remedial action plan. The remedial action plan is a cleanup plan that lists the pertinent BUIs, the criteria for restoring them, and the specific projects that are necessary to implement to address and their removal. As identified in the St. Louis River AOC remedial action plan, the Kingsbury Bay shallow sheltered embayment project will contribute to the removal of the degraded fish and wildlife populations, and loss of fish and wildlife habitat.

Over the past 80 years, Kingsbury Bay has become increasingly shallow due to sediment flowing from the Kingsbury Creek watershed into the bay. Currently, the head of Kingsbury Bay is only about 1 foot deep although it used to be closer to 3 feet deep on average. This shallowness allowed invasive cattail to dominate the emergent vegetation in the bay, which has reduced the value of the habitat for benthic invertebrates and fish, as well as limiting access to the bay for recreational users.

Restoration of Kingsbury Bay will include dredging of sediment to restore Kingsbury Bay’s historical bathymetry, removal of the invasive cattail stands, and planting of a diverse, native emergent wetland community. These actions will return Kingsbury Bay to a high quality shallow sheltered embayment habitat that will allow benthic organisms, aquatic vegetation, fish, and wildlife to grow, survive, and reproduce. Additionally the restoration project includes recreational access components such as a fishing pier that will compensate the public for recreational fishing losses at the St. Louis site.

The Kingsbury Bay restoration project is part of a larger, integrated restoration project referred to as the Kingsbury Bay-Grassy Point project. The approximately 180,000 cubic yards of sediment that will be removed from Kingsbury Bay are slated to be used as clean fill at the Grassy Point habitat restoration project just downstream in the St. Louis River. The clean fill will serve as an ideal substrate for the recolonization of native aquatic plants and provide habitat for benthic invertebrates at Grassy Point once large volumes of wood waste are removed. The transfer of clean sediment from Kingsbury Bay to Grassy Point requires close coordination in design, and construction of both projects.

During the assessment phase of the St. Louis River Interlake/Duluth Tar site NRDA, the trustees identified the Kingsbury Bay project as an excellent restoration site to address injuries incurred at the St. Louis site. At that stage, the trustees began conversations with the St. Louis River AOC Coordinator Team, which includes a representative from Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Through close coordination with that team, and other stakeholders, including the City of Duluth and the Minnesota Land Trust, the trustees developed a collaborative design for Kingsbury Bay. These intense coordination efforts resulted in a design that will first and foremost address the injuries from PAH contamination at the St. Louis site, but also aligns with the Kingsbury Bay project objectives that will move the St. Louis River site toward recovery.