In the U.S., it has been a fact of life that major news events influence the political course of the country. Occurrences large and small can stir the notoriously short and fickle attention span of the public, and in turn, the political machinery that generally responds to what the voters believe to be issues of importance. Oil spills may sometimes rise to that level, depending on their size and complexity. As such, American oil spills have had a history of inspiring significant pieces of legislation that have established the foundation of environmental safeguards that have (mostly) endured intact to protect natural resources and the health and safety of the American public.

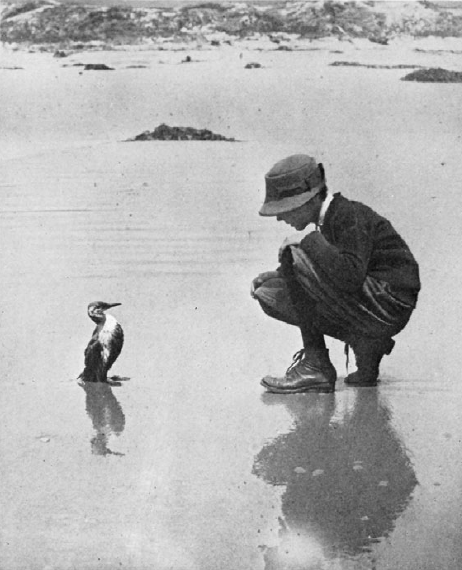

Bilge Oil and Birds

Even prior to large oil spills occurring and becoming associated as a cost of our growing use and dependence on petroleum, there was a recognition that oil was capable of harming fish and wildlife.

On the West Coast, the California Fish and Game Commission wrote in 1917 that “Pollution of ocean waters, due to the pumping of bilge water and emptying of ballast tanks still continues. Not only do many sea birds fall victims to the oil on the surface of the water, but this oil also destroys the plankton used as food by many valuable food fishes.”

The lavishly illustrated 1923 guide book, The Birds of California, by William Leon Dawson, included some pointed commentary about oil in the water:

For two decades now it has been the practice of oil-carrying ships, “tankers,” to heave to and clean out before entering the Golden Gate. To be sure the practice is illegal, but when does a great corporation stoop to regard so trifling a thing as the law? And if the necessity were explained to them, what average lot of sea-faring men would regard the welfare of a few bobbing sea-fowl? Commerce is master and the interests of men are subsidiary. Well; the Murres are nearly done for. The birds must swim, and they must appear for breath upon the surface of the water, where the loathsome crude oil attaches itself like pitch to their immaculate plumage. It smears the belly, it engages the flight-feathers, it impedes action. The frightened bird drags itself ashore to cleanse its plumage. But all it succeeds in doing is to involve the alimentary canal in the slimy infection. Purging and starvation follow, and the lawless tankers have nearly made a bird-less waste of a region which was once a wonder of the scientific world.

On the East Coast, the New York Times reported in 1922 that oil discharged with ballast water had become such an increasing problem that it “defiles everything it touches …The pollution thus created is a menace to fish, wild fowl, health, and sanitation.” The pollution was so widespread and of such an alarming scale that Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1924, which outlawed oil discharges from vessels into navigable waters of the U.S. for the first time, and authorized punishment and fines. However, the 1924 law was narrowly focused; it took another 37 years, until the Oil Pollution Act of 1961, to expand the scope of oil discharge prohibition (within 50 miles of land), and to add regulations for installation of equipment and requirements for record-keeping. The spectre of accidental oil releases of the scale we now find familiar was still unknown, and therefore, unaddressed by U.S. legislation.

Torrey Canyon, 1968

Oil spills of the type and size that we have unfortunately become accustomed to are a relatively modern occurrence, and had their beginnings in England in 1967 with the wreck of the tanker Torrey Canyon. An estimated 119,000 metric tons (around 37 million gallons) of crude oil spilled into the waters off the southern coast of England, resulting in a massive but haphazard response. This, of course, was not an American incident, but its repercussions were felt across the Atlantic and made their way into U.S. law in the form of the 1968 creation of the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan (more commonly referred to as the National Contingency Plan, or NCP). The NCP is the federal government's blueprint for responding to both oil spills and hazardous substance releases. Among other features, the 1968 plan devised approaches for spill reporting, containment, and cleanup; and created precursors to the National Response Team (NRT) and Regional Response Teams (RRTs) that guide U.S. response today.

Union Oil Platform A, 1969

The first large U.S. oil spill occurred just two years after the Torrey Canyon incident, off the coast of Santa Barbara, California. A Union Oil production platform six miles southwest of Santa Barbara experienced a gas blowout, and when workers attempted to seal off the well, pressurized oil and gas began leaking through fissures in the underlying bedrock. Due to the multiple-source nature of the oil release, through those cracks in the seafloor, it was difficult to estimate the total amount of oil released over the course of the week and a half before the well itself could be sealed. NOAA later estimated a range for the amount of oil spilled as between 33,000 and 100,000 barrels, or 1.4 and 4.2 million gallons.

The Santa Barbara spill was a grim wakeup call for an American public that had not experienced such an event. Occurring, as it did, in an affluent and picturesque coastal community that was home to a rich wildlife assemblage, the spill received unprecedented news coverage. The front pages of newspapers and lead stories on evening television news broadcasts showed images of oil-soaked birds and idyllic beaches and marinas despoiled with thick black California crude oil. President Richard Nixon eventually visited the area and toured the cleanup.

The Platform A/Santa Barbara spill is widely credited as being one of the major drivers behind the launching of the American environmental movement. While 1969 saw other graphic examples of environmental decline in the country (e.g., the highly-publicized ignition of the polluted Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio), the Santa Barbara oil spill received nationwide media coverage, resulting in a significant public outcry.

Following rapidly in the wake of the oil spill was the signing of the National Environmental Policy Act (which established national environmental policy and goals for the protection, maintenance, and enhancement of the environment) in early 1970; the inaugural Earth Day celebration in April, 1970; the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the same year; and the 1972 passage of the Clean Water Act (which set the basic structure for regulating discharges of pollutants into the U.S. waters and regulating quality standards for surface waters). It was an era of energized environmental consciousness, including at the Congressional level: other benchmark environmental legislation key to NOAA’s stewardship responsibilities was also enacted during this time, including the Marine Mammal Protection Act (1972); the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act (1972); and the Endangered Species Act (1973).

Exxon Valdez, 1989

Prior to 2010 and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the Exxon Valdez spill stood as the benchmark against which all other U.S. spills and spill responses would be measured: in scale, scope, animus, hubris, cost, controversy, and generally bad karma. On Thursday evening, March 23, 1989, the fully-loaded tanker Exxon Valdez departed the Alyeska Pipeline Terminal in Valdez, Alaska. Just after midnight on March 24—Good Friday—the vessel went hard aground on Bligh Reef, at the southern end of Valdez Narrows. The force with which the tanker hit the charted reef would later be revealed in the shipyard of National Steel and Shipbuilding in San Diego, where repairs would be made: two pieces of Bligh Reef remained lodged in the heavily damaged hull and frame of the Exxon Valdez, one of which was the size of that universally-understood metric, a Volkswagen Beetle.

The Exxon Valdez would release around 262,000 barrels (11 million gallons) of Alaska North Slope crude oil into the waters of Prince William Sound. There was a brief opportunity to engage in major cleanup of the oil on the water; but federal, state, and Exxon responders were not well-prepared to deal with a spill of this magnitude. While plans to deploy large-volume response methods like dispersant application and in-situ burning were considered and tested, the advent of a large storm that quickly spread the oil across Prince William Sound and beyond, necessitating the shift from an on-water response to shoreline cleanup. The latter activities would extend through 1989, 1990, and 1991, interrupted only by the harsh Alaskan winters. The toll inflicted by the spill on birds and other wildlife like sea otters, documented by news media across the country and around the world, as well as the length of time required for the shoreline cleanup, resulted in high visibility and constant public awareness. Eventually, these would translate into congressional action and new legislation related to how the U.S. government would respond to oil spills.

Attempts to consolidate what had been a patchwork of laws governing oil in the environment had been regularly introduced for consideration in Congress through the 1970s and 1980s (a modest effort called the Oil Pollution Act of 1973 was signed into law by President Nixon, but like the bill in 1924 focused on vessel discharges of oil and brought the U.S. into compliance with international laws). Comprehensive oil spill legislation to update and consolidate oil spill preparation, planning and response generated little interest and was not seriously considered. However, the Exxon Valdez and other spills occurring in 1989 and 1990 changed that dynamic. With shoreline cleanup still incomplete on the beaches of Prince William Sound, the Oil Pollution Act was passed by both houses of Congress in November of 1989; it took until August 1990 for the House and Senate to reconcile differences in their respective bills, but the final version was passed unanimously and President George H.W. Bush quickly signed it into law the same month.

The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA90) fundamentally changed how the U.S. responded to oil spills. The legislation addressed critical, if unglamorous, details of oil spills such as liability and damages and regulatory changes. But in implementation and in practice, these resulted in definitions of responsible parties in the event oil is spilled, determined who pays for cleanup, established the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund (OSLTF) that pays for cleanup when a responsible party cannot or will not; specified that OSLTF would pay for damage assessment and restoration activities, eventually resulting in the creation of Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA); required double-hulls on tankers operating in U.S. waters; empowered the U.S. Coast Guard with enforcing provisions of OPA90 regulations (the largest expansion of its law enforcement duties since Prohibition); recommissioned and strengthened the Coast Guard Strike Teams for rapid response. And a very specific provision in the sweeping federal law: “Notwithstanding any other law, tank vessels that have spilled more than 1,000,000 gallons of oil into the marine environment after March 22, 1989, are prohibited from operating on the navigable waters of Prince William Sound, Alaska.” This statement in federal law effectively prevented the Exxon Valdez from ever operating again in Alaskan waters over the course of its remaining time at sea.

Deepwater Horizon, 2010

Ten years have passed since the nation’s largest and possibly most contentious marine oil spill, which occurred in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico and then made its way to the shorelines and marshes of Gulf coast states. Billions of dollars in damages have been litigated, assessed, and paid, and the unprecedented research programs funded by BP and damage assessment investigations are coming to a close. The other defining oil spills we have featured here resulted in significant, groundbreaking new laws and regulations, and certainly there was that expectation for the largest spill response in history that occurred for the Deepwater Horizon.

But.

It didn’t happen. We can debate the reasons why the massive Deepwater Horizon spill did not elicit the kind of unified and decisive Congressional response that seemed to be the norm for the modern history of oil spills in the U.S. But the reality is that there is legislatively little to show for this one iconic American oil spill. In 2012, Congress passed the Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States Act (RESTORE Act), which allocated most of the Deepwater Horizon administrative and civil penalties to a restoration trust fund. In 2016, the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) adopted stricter regulations governing the blowout preventers installed on production wellheads as a last line of defense in the event of an uncontrolled release, and tightened well control requirements (these regulations were relaxed in 2018).

On the industry side, there was a recognition that as oil exploration and production moved into increasingly deeper water, response capabilities needed to be upgraded. In 2010, 10 petroleum-related companies collaborated to create and fund a new response entity, the Marine Well Containment Company, This nonprofit company focuses on providing equipment and personnel to respond to deep water (up to 10,000 feet) blowouts like the Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico, maintaining a stockpile of so-called “capping stacks” that are capable of shutting off the flow of oil and gas from an uncontrolled well.

The long-lasting legacy of an oil spill

In the lexicon of social science and political science, there is a concept called the “issue attention cycle.” This view of the world, created by economist Anthony Downs of the Brookings Institution, defines a cycle in which each of a series of domestic problems “… suddenly leaps into prominence, remains there for a short time, and then … gradually fades from the center of public attention.” Downs postulated that how long the public remains interested in the issue determines whether there is enough political pressure to cause effective change.

In most cases, major oil spills have crossed the threshold to engage and sometimes enrage the public to the extent that the political machinery produces real and significant change. Much of the environmental protection that is institutionalized in American law owes at least some of its heritage to oil spills. This can be thought of as a silver lining to environmental mishap and disaster, and perhaps the longest-lasting legacy of an oil spill.