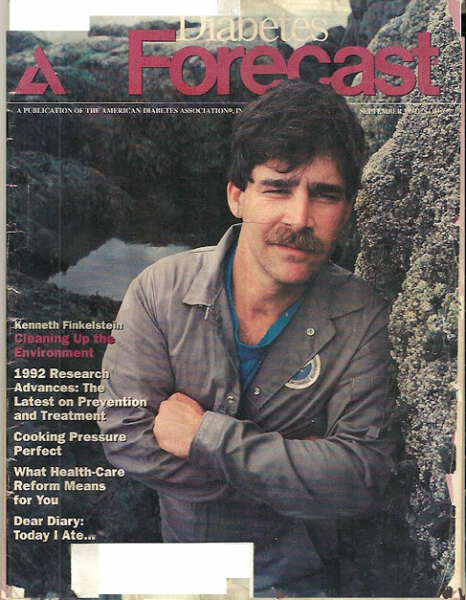

This feature is part of a monthly series profiling scientists and technicians who provide exemplary contributions to the mission of NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration (OR&R). In our latest "Minds Behind OR&R," we feature Regional Resource Coordinator Ken Finkelstein.

Ken Finkelstein likes solving crossword puzzles, sudoku, and using logic to solve problems. It’s this drive, and a competitive streak, that fueled his 37-year career at NOAA.

“I love the competition found in a field of science where data interpretations will vary.” Ken said, “If you come prepared, really know your science, it’s possible to ultimately get important restoration done.”

Ken grew up in New York City at the bottom of a steep moraine, made up of rocks and soil deposited by glaciers, and his friends lived at the top. Biking up and down it made him wonder how that hill came to be. He also remembers swimming at Jones Beach on Long Island during the summers, how the current would always drag him down the beach-away from his towel. These experiences first piqued his interest in coastal geology.

New York City also left a mark on his personality. “When you grow up in New York in the 1970s you feel invincible, just riding around in the subways was an adventure,” Ken said. As a geology major at SUNY-Stony Brook he spent two summers driving an ice cream truck around NYC—if you want stories, Ken’s got them!

While Ken had achieved high grades as an undergrad, his master's program at the University of South Carolina taught him how to be a scientist.

“I found something I loved to do, learning how to think” Ken said.

Halfway through his first year a twist of fate pointed to a career towards oil spills. There was an active oil spill, Amoco Cadiz, in France, and Ken was the only graduate student in his lab who had a passport and could drive a stick shift.

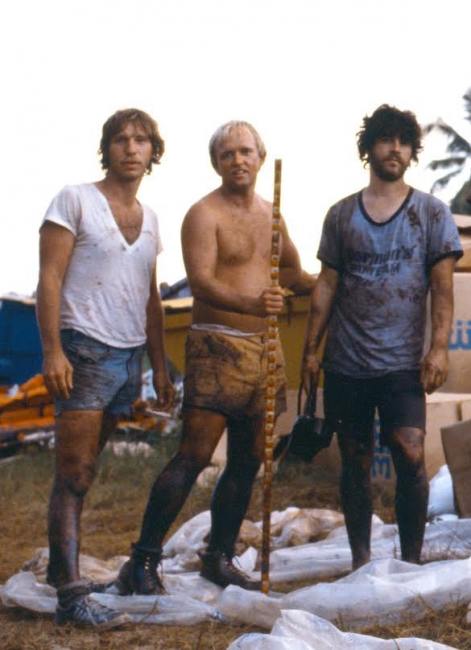

In 1978, the Amoco Cadiz oil spill, one of the largest of all time, spilled an estimated 220,880 metric tons of oil along the picturesque coast of Brittany. Ken’s advisor worked with NOAA to study the residence time, the amount of time a liquid stays in a vessel, of oil and called Ken because all the rental cars were manual transmission. The next morning he was off to France, the youngest on a team trudging through beaches smothered with thick, black oil. They were doing shoreline cleanup assessment technique (SCAT) before there was a name for it. It was an exciting time.

“Over the next year and a half I went to France, Portugal, Alaska, Puerto Rico, and the Texas shoreline for the IXTOC I spill. For a kid that grew up in NYC I was suddenly traveling all over the world!” Ken said.

After graduation he moved to Washington D.C. to work for the Army Corps of Engineers, until Ronald Reagan proposed moving the entire agency to Mississippi.

“I was 27, single, and that didn’t seem like a good choice. So I went back to school,” Ken said.

At the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences at William & Mary, Ken examined nearly 100,000 years of barrier island geology, piecing together a story about the depositional environment by examining the stratigraphy, carbon-14 dates, pollen, and microorganisms in approximately 100 sediment cores. Ken says that pursuing a dissertation is an opportunity to study one scientific question for several years. It’s a once in lifetime decision and opportunity and although personal sacrifices are made, the result was tremendously rewarding.

“Although very few people do Ph.D. research that changes the world, you contribute to science and that’s an accomplishment," Ken said.

In addition to his research, Ken owned a small sailboat in Virginia and met his soon-to-be wife who was a lawyer in Boston. Following a joint trip to Australia to deliver a conference presentation, and later to the South Pacific, Ken moved to Boston. There he accepted a job with NOAA in 1987 assessing the environmental impacts of hazardous waste sites, despite having little experience in the field.

“My greatest accomplishment was shifting careers from coastal geology to environmental chemistry and the additional varied technical skills required as a regional resource coordinator,” Ken said.

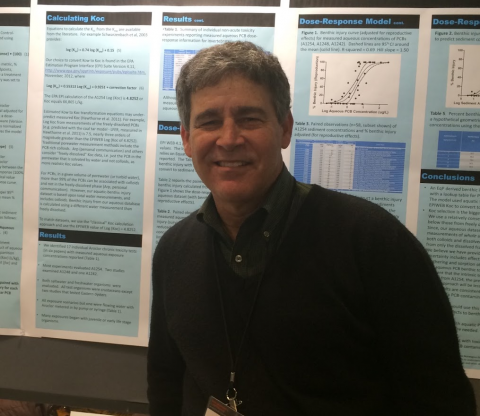

Many at OR&R know Ken today as a 34-year veteran of NOAA with many respected publications, including several in the field of ecotoxicology. Most recently he published an innovative approach evaluating the impacts of PCB-contaminated sediment on benthic life. But when he first started, Ken didn’t put "Ph.D." next to his name because he didn’t want anyone asking him questions he couldn’t answer. He learned on the job, attending every presentation he could, reading the literature, taking extensive notes, and preparing for every meeting so he wouldn’t be caught off guard. Eventually, he felt like he earned those letters.

Over the decades Ken has worked on many cases. He was brought onto the Exxon Valdez spill doing beach surveys in the exact same location where he’d helped with graduate research.

“What stands out in my memory was the hot water, high pressure, cleaning and how slippery it got on the beaches. And being there 10 years earlier—remembering how stunning it had been—the damage from the oil was really striking,” Ken said, adding that he also assisted with the Deepwater Horizon assessment in 2010. “I was the youngest guy at Amoco Cadiz and an old man at Deepwater Horizon,” Ken laughed.

Ken has also worked on many notable hazardous waste sites across Massachusetts and the Northeast Region. The Nyanza site was memorable because he published research tracking the growth rate of mussels caged in the mercury-contaminated Sudbury River. New Bedford Harbor also stands out because of the record-high levels of PCB contamination and the $20.4 million settlement for restoration Ken helped reach in 1992.

Overall, Ken says Atlas Tack was his favorite site because he worked closely with his Environmental Protection Agency partner Elaine Stacey to include restoration as part of the EPA mitigations efforts. This helped the site in Fairhaven, Massachusetts recover more quickly from heavy metal contamination. The pair won two EPA Superfund Bronze Medal awards for their work.

In addition to working at NOAA, Ken also taught oceanography part-time at Suffolk University in Boston for 32 years, switching to Framingham State University this year. He has also been involved, as a coach and now a judge, with the NOAA Science Bowl, a national science education and outreach event that encourages students to learn about the natural world.

“Ken is a natural teacher,” said Diane Evers, ARD’s Northeast regional manager. “Whenever he’s answering a student’s question you can just see him light up. It’s the same energy that he brings to working with teams at NOAA. Not only is he a great scientist, he values passing on scientific knowledge to others.”

Looking back on his 37-year career in the federal service, 34 of which has been with NOAA, Ken is most proud of the restoration projects he’s helped to implement across the Northeast.

“It was and remains a really great job," Ken said. “Sometimes I think about what I would do if I retired, and I don’t want to play golf every day. I’m already doing what I want to do.”