As a sea kayaking enthusiast who enjoys paddling the waters of Washington’s Puget Sound, I need to have up-to-date information about the currents I’m passing through. Accurate predictions of the strong tidal currents in the sound are critical to safe navigation, and kayak trips in particular need to be timed carefully to ensure safe passage of certain regions.

As a NOAA oceanographer and modeler, I also depend on accurate information about ocean currents to predict where spilled pollutants may travel in the marine environment.

Sound Information

These are two reasons I was excited to learn that NOAA’s Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services(CO-OPS) is performing a scientific survey of currents in the marine waters of the Puget Sound, the San Juan Islands, and the Strait of Juan de Fuca. They began in the south sound in the summer of 2015, deploying almost 50 devices known as Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers to measure ocean currents at various depths throughout the water column.

Work is getting underway this summer to continue gathering data. The observations collected during this survey will enable NOAA to provide improved tidal current predictions to commercial and recreational mariners. But these updated predictions will also help my line of work with oil spill response.

When oil spills occur at sea, NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration provides scientific support to the Coast Guard, including predictions of the movement and fate of the oil. Accurate predictions of the oil trajectory may help responders protect sensitive shorelines and direct cleanup operations.

Spills Closer to Home

In the last few years, I’ve modeled oil movement for numerous spills and traveled on scene to assist in the oil spill response.

Seeing oil on the water and shorelines of places ranging from Santa Barbara, California, to Matagorda Island, Texas, I can’t help but think about both the possibility of a spill closer to my home in Puget Sound and our ability to model the movement of the oil there.

When oil spills in the marine environment, it spreads quickly, forming thin slicks on the ocean surface that are transported by winds and currents.

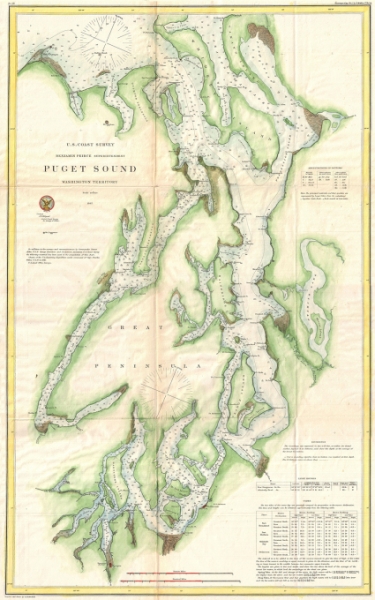

Puget Sound is a glacially carved fjord system of interconnected marine waterways and deep basins separated by shallower regions called sills.

Tidal currents in these narrow, silled connection channels can reach fairly swift speeds of up to 5-6 mph, whereas in the deep basins the currents are much slower (typically less than 1-2 mph).

Accurate predictions of currents within the sound will be critical to forecasting oil movement. Today’s predictions for this region rely on limited amounts of data gathered from the 1930s-1960s. Thanks to both these current surveys and modern technological advances, we can expect significant progress in the accuracy of these predictions.

The information collected on the NOAA current surveys will also be used to support the creation of an Operational Forecast System for Puget Sound, a numerical model which will provide short-term forecasts of water level, currents, water temperature, and salinity—information that is critical to oil spill trajectory forecasting.

Making Safer Moves

More accurate current and water level predictions are good for oil spill modeling, but they are even better for oil spill prevention by making navigating through our waterways safer.

Until fairly recently, 90% of the oil moving through Washington (mainly to and from refineries) traveled by ship. But by 2014, that number dropped to less than 60%, with rail and pipelines making up the difference.

Because the methods for transporting oil through Washington are shifting, the risks for oil spills shift as well. However, even with the recent increase in crude oil being delivered by train, the number of vessels transporting oil through state waters has gone up as well, increasing the risk of a large oil spill in Puget Sound.

With such a dynamic oil transportation system and last December’s repeal of a decades-long ban on exporting U.S. crude oil, the Washington Department of Ecology has decided to update its vessel traffic risk assessment for the Puget Sound. Results from the risk assessment will ultimately be used to inform spill prevention measures and help us become even better prepared to respond to a spill.

The takeaway? Both state and federal agencies are working to make Washington waters safer.

Amy MacFadyen is a physical oceanographer at the Emergency Response Division of the Office of Response and Restoration (NOAA). The Emergency Response Division provides scientific support for oil and chemical spill response — a key part of which is trajectory forecasting to predict the movement of spills. During the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, Amy helped provide daily trajectories to the incident command. Before moving to NOAA, Amy was at the University of Washington, first as a graduate student, then as a postdoctoral researcher. Her research examined transport of harmful algal blooms from offshore initiation sites to the Washington coast.