This blog was originally published on Sept. 3, 2021.

The International Coastal Cleanup is coming up on Sept. 18, 2021, when volunteers around the world will be cleaning beaches and shorelines of the debris that has accumulated there. In addition to these organized events, there are also many people who generously take it upon themselves to pick up trash when they visit beaches or shorelines.

So, what do these kind volunteers and beach-goers find? Lots of cigarette butts, food wrappers, and single-use water bottles, but also, some weird and interesting things.

Here in NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration (OR&R), we recently heard from two individuals who found some interesting things while cleaning up trash, and they wrote to tell us about them!

Fred Barrow in France

On Aug. 8, Fred Barrow participated in a shoreline cleanup in France coordinated by his daughter Salomé Barrow and sponsored by the Surfrider Foundation Europe. The cleanup took place on Oleron Island (French Atlantic coast) in Gatseau Bay. Fred was intrigued by one of the pieces of debris that was found and reported to us the group’s interesting find.

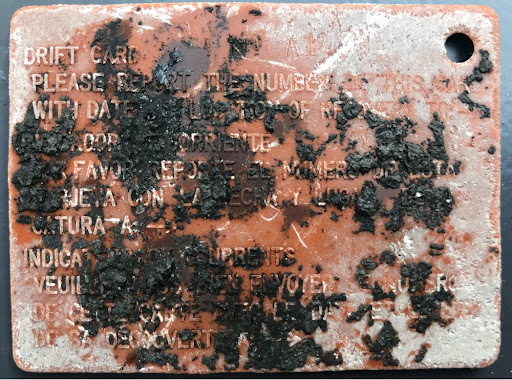

One of the cleanup volunteers, 17-year-old Rose Deragne, spotted a brightly colored plastic card with raised lettering. She found the card on a sandy dune on the southern tip of the island. The card contained almost illegible instructions to report the number of the card with the date and location of recovery to the NOAA OCSEA Program Office in Boulder, Colorado. That program no longer exists, but Fred helped out by tracking down our office.

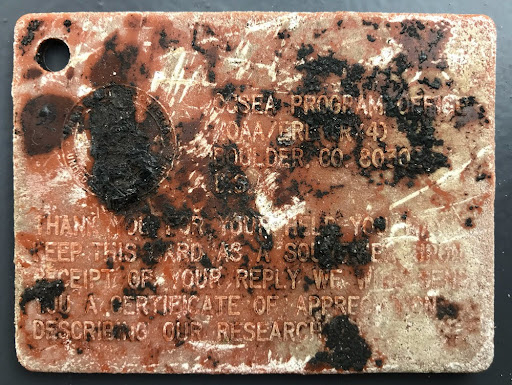

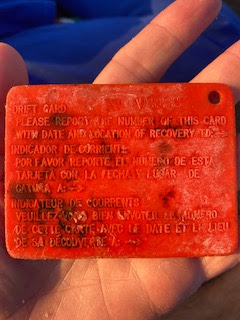

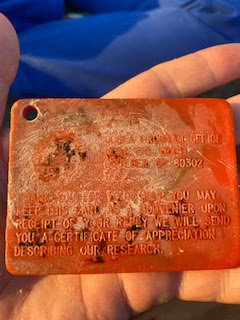

The front side of the plastic drift card (above) was found on Oleron Island, France on Aug. 8, 2021. Although difficult to read, the front side of the card contains this information: "Drift Card No. [illegible]. Please report the number of this card with date and location of recovery to: (turn card over)" The instructions are also provided in Spanish and French. Although difficult to read, the back of the drift card (click below to enlarge) shows the logo for the U.S. Department of Commerce and the following information: “OCSEA Program Office NOAA/ERL (RX4) Boulder, CO. 80302 U.S.A. Thank you for your help. You may keep this card as a souvenir. Upon receipt of your reply, we will send you a certificate of appreciation describing our research.”

Pierre Gauthey in the Azores

French citizen Pierre Gauthey was on holiday in Terceira Island in the Azores (Portugal) with his family on Aug. 14. As an avid surfer, Pierre seeks out challenging surf spots, and on that day, the forecast was for good surfing in a spot known as Quatro Ribeiras, on the north side of the Island. It is a wild, dangerous, and difficult-to-access location, a few kilometers from the town of Quatro Riberas.

Pierre explained that you can access the spot through a track road that ends on a beach of volcanic rock and stones. After parking your vehicle, you have to walk on the stones along the beach for 300 meters. Coming to a big cliff that has partly collapsed, you have to clamber over big rocks for about 300 more meters until you reach another beach, this one made of round black stones, most of them bigger than a basketball. There used to be a direct access to this beach from the cliff, but the trail collapsed during a big storm a few years ago, so now it’s a surf spot you can access only after 30 minutes of hard walking/climbing.

Once on the beach, there is no sand, and the waves are violent. It is a wild and beautiful environment, well protected from the crowds, and definitely a spot for experienced surfers only. Pierre reports that, aside from the occasional surfer and some fishers or shellfishers, he is often alone there.

When Pierre arrived at the surf spot the tide was too high, so he waited. As he often does, he started picking up trash he found on the beach, to pack out when he left. He explains, “I am very concerned about environmental issues and this is a way to contribute. I teach my kids to do it, as well. … I really think that if everyone would pick up three pieces of plastic waste each time they go to the beach, the planet could be cleaned up very fast.”

Among the debris Pierre found between the rocks—plastic bottles, polystyrene, and thongs (plastic flip-flop shoes)—was a strange orange plastic card with a message on it. Back at home, he tried scrubbing the dirty card in order to read the message, and was disappointed to watch the raised lettering on the card—weathered and brittle after years in the sun and salt—crumble away. But, he could still read “NOAA,” so his online research brought his discovery to us.

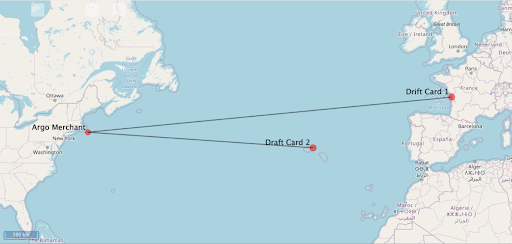

This map shows the distance from the spill site (29 miles southeast of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, U.S.A.) to the locations where drift cards were found: (1) the southern tip of Oleron Island in Gatseau Bay, France and (2) the north shore of the island of Terceira in the Azores (Portugal). The cards likely crossed the Atlantic within a year or two of being deployed and may have been buried on a shoreline or in sand until storms uncovered and remobilized them.

Help for Spill Responders

The scientists in OR&R are familiar with these cards, although found cards are reported very rarely now. Over 10,000 of these cards were released by NOAA back in 1976 on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. The drift cards were released from the air between Christmas and New Year, in an effort to track the oil spilled from the tanker Argo Merchant. In high winds and ten foot seas, the ill-fated Argo Merchant ran aground, broke apart, and spilled its entire cargo of fuel oil southeast of Nantucket Island on Dec. 15, 1976.

The colorful drift cards were intended to serve as an early warning system and visual reference to NOAA oceanographers, to indicate when and where the wind was threatening to blow the oil onto the shorelines. Thankfully, prevailing winds and currents carried the spilled oil away from the shorelines and fisheries of Nantucket; however, weather conditions and uncharted depths surrounding the wreck made salvage attempts difficult. (View historical images from the Argo Merchant spill, and learn more about the spill and its response.)

OR&R has received other reports of drift cards found from the Argo Merchant incident (PDF), including the report from retired postman Chris Easton, who spotted a card on a Cornish (UK) beach in 2014. That report was being considered for a distance/longevity record in the Guinness Book of World Records, so it’s possible that Fred’s report—7 years later and about 500 miles more distant—may become the new record!

Drift card studies have been conducted by various NOAA offices over the years, including several studies by OR&R, and even by some young non-governmental scientists. OR&R’s most recent studies didn’t involve the use of plastic cards, however. Instead, identifying information was marked on thin, biodegradable pieces of wood, colored with bright non-toxic paint. Finding aging plastic, such as this card, on a beach or shoreline clearly illustrates the persistence of plastic in the ocean.

If you’ve never scooped up some trash or participated in a coastal cleanup, we encourage you to give it a try! You will vastly improve a local shoreline by clearing it of debris, while also spending time with like-minded people. And, you just might find something really cool—or even historic!

Additional Resources:

Here is a series of six stories examining the oil spill in 1976 of tanker Argo Merchant, resulting in the creation of the Office of Response and Restoration.

- Emergency Response and Assessment 40 Years after Argo Merchant

- Argo Merchant: The Growth of Scientific Support

- Argo Merchant: The Birth of Modern Oil Spill Response

- Tools and Products: 40 Years of Spill Technology

- Argo Merchant: What if it happened today?

- Argo Merchant: A Woods Hole Scientist's Personal Perspective