A whale breaching out of icy water, a sea turtle crawling onto the sandy shore to lay eggs, or a salmon swimming upriver to spawn, few species capture our hearts and imaginations more than protected species. However, it wasn’t until relatively recently that they were protected under U.S. law.

NOAA is a steward for marine wildlife like sea turtles, whales, dolphins, and other marine mammals that swim through U.S. waters. NOAA’s Office of Protected Resources works under environmental regulations, such as the Endangered Species Act and Marine Mammal Protection Act, that provide the legal framework needed to conserve these protected species.

A Brief History of the American Environmental Movement

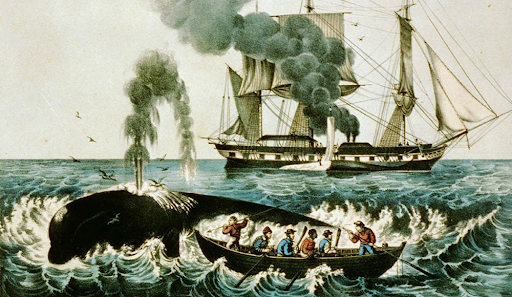

For much of our history, non-Indigenous Americans generally viewed natural resources as having an unlimited supply. During expansionism and the industrial revolution, people saw natural resources as things to be tamed and profited from in the name of progress. Whaling killed millions of animals for oil off the East Coast, sea turtles were harvested for their shells, and sea otters were slaughtered for their pelts. Marine mammals and sea turtles became part of a new commercial industry that was at a greater scale than traditional harvesting for food or cultural purposes by Indigenous peoples.

This attitude began to change in the mid-1900s when the unregulated effects of industrial “progress” took its toll on our environment. People started to see wildlife as having their own, inherent value. By the 1960s, the United States began transitioning into the modern era of wildlife and environmental protections. During the 1970s environmental movement, which also led to the creation of NOAA, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and many environmental nongovernmental organizations, the idea of protecting our natural resources became mainstream.

Significant increases in new laws designed to protect the environment resulted from the changes occurring in the 1960s and 1970s. Federal agencies also increasingly began playing a vital role in regulating and protecting our natural resources, which illustrates the importance placed on conservation from this era.

In particular, NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) is responsible for regulating and protecting over-exploited, threatened, and endangered species through the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) of 1972 and the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) prohibits U.S. citizens and entities from “taking” and importing marine mammal species, with certain exceptions, and establishes a national policy to prevent marine mammal species and population stocks from declining beyond the point where they cease to be significant functioning elements of the ecosystems of which they are a part.

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) provides a framework for the conservation of threatened or endangered species (“listed species”) and the habitat that is critical for their existence ("critical habitat"). The ESA requires all federal agencies, in consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and/or NMFS, to ensure that actions they authorize, fund, or carry out are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any listed species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of designated critical habitat of such species.

The law also prohibits any action that causes a "taking" of any listed species of endangered fish or wildlife. Likewise, import, export, interstate, and foreign commerce of listed species are all generally prohibited.

The MMPA and ESA have been effective conservation laws. Due to the success of the MMPA, the status of many marine mammal populations has greatly improved since 1972, as there are fewer marine mammals within U.S. waters listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in “at-risk” categories and more in the categories of “least concern.” Additionally, due to the successes of the ESA, over 98% of species listed as “threatened” or “endangered” have been prevented from going extinct.

The Logistics of Protecting Species

The NMFS Office of Protected Resources is organized into five Divisions (internally known as PR1-PR5) and is responsible for implementing the MMPA and ESA to ensure that everyone, including scientists, commercial fishermen, industry, and other federal government agencies, including NOAA, are following the requirements of the statutes. The MMPA and ESA are also comprised of many sections, and different sections of these Acts may apply to different activities and/or entities. Different sections of these Acts may be implemented by different divisions within the Office of Protected Resources. For our purposes, we’ll focus on requests for “take” of marine mammals for activities that may either directly or incidentally result in such take under the MMPA, and on requests for consultation from Federal agencies for activities that may affect threatened or endangered species and/or that may adversely modify designated critical habitat for these species under the ESA.

The Permits and Conservation Division (also known as “PR1” internally) is responsible for reviewing requests for authorization of indirect (or “incidental”) and direct “takes” under specific parts of the MMPA, and the ESA Interagency Cooperation Division (also known as “PR5” internally), is responsible for intra- and inter-agency consultations under section 7 of the ESA for actions that are national in significance, would affect more than one NMFS region, affect foreign listed species, among other factors. Typically, ESA section 7 consultations for individual projects and region-specific actions take place in the region of the proposed federal action.

“Taking” Protected Species:

The MMPA and ESA prohibit “taking” of protected species. The legal definition of “take” differs somewhat between the MMPA and ESA (see below), but generally speaking unauthorized “taking”, or harming an endangered species is a crime that may be punishable by jail time and/or fines under both statutes.

That’s why whenever someone wants to do something that may affect protected species, such as funding or undertaking a project that may affect an ESA listed species, or conducting a scientific field study of whales, they need to coordinate with the NOAA Office of Protected Resources. PR1 reviews requests for directed or incidental “take”, as required under Sections 101 and 104 of the MMPA, respectively, and PR5 (or the appropriate regional office) consults under Section 7 of the ESA when a Federal agency determines an activity they will fund, authorize, or undertake may affect a listed species, or would adversely modify any listed critical habitat, and requests consultation.

Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act

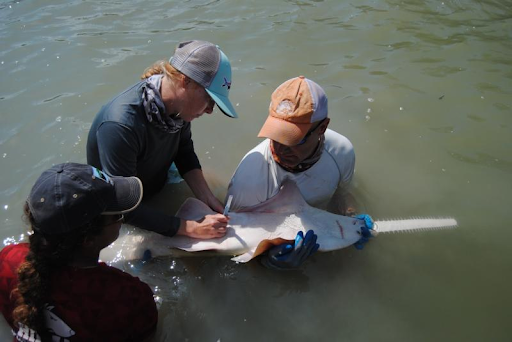

Section 7 of the ESA requires all Federal agencies to consult with NMFS if any of their actions (that they are doing, funding, or authorizing others to carry out) may affect an endangered or threatened species or adversely impact habitats critical for their survival. Whether the proposed action may benefit listed species, such as if a NOAA researcher wants to capture sea turtles to study their health, or may harm species, such as if the Department of Transportation wants to fund building a road through coastal wetlands, all actions that may affect listed species require a Section 7 consultation. The consultation evaluates all of the potential effects of the action, including those occurring at the same time as the proposed activities and those that may occur later in time than the action, and may include consequences occurring outside the immediate area involved in the action.

Let’s say the Department of Transportation wants to fund building a dock on a river where migratory salmon are found at certain times of the year. The construction of the dock might only impact salmon for part of the year, but the effects of the dock may continue to affect salmon for the functional life of that dock. In addition, the dock may increase vessel traffic both in terms of increasing the number and/or size of vessels accessing the area, which may have impacts outside of the immediate area of the proposed dock. These effects all need to be taken into account as part of the consultation to determine whether the activity would jeopardize the continued existence of the salmon or adversely modify any critical habitat for the listed salmon species, if any is present.

However, Section 7 consultations are only with federal agencies because this section of the Act does not apply to private actions. Other section(s) of the ESA may apply to private actions (such as Section 10), but the only way a potential private project would require a Section 7 consultation would be if a Federal permit/authorization is required as part of the action; if any Federal funds would be used for the activity; and/or if there is a Federal approval or permit required for the activity.

While Section 7 of the ESA only applies to federal agencies, the ESA prohibits anyone (including private citizens) from “taking” listed species, which is defined by the Act as harassing, harming, pursuing, hunting, shooting, wounding, killing, trapping, capturing, or collecting, or to attempting to engage in any such conduct, without an “Incidental Take Statement” being issued by the Services (NOAA or US Fish and Wildlife Service, depending on the species in question) for such “take.”

Sections 101 &104 of the Marine Mammal Protection Act

With some exceptions, the Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibits the” taking” of any marine mammal species. “Take” is defined by the MMPA as harassment, hunting, capturing, collecting, or killing – or attempting to harass, hunt, capture, collect, or kill any marine mammal. The MMPA applies to all species of marine mammals, including those that are not ESA-listed species, and applies to all U.S. citizens and entities.

Sections 101 and 104 of the Act allow for exceptions to the prohibition of “take” of marine mammals.

Section 104 of the MMPA may authorize take for actions directed at marine mammals, like:

- Commercial or educational photography;

- Public display at aquariums;

- And scientific research on marine mammals.

Section 101 of the MMPA may allow for take of marine mammals that is incidental to other actions, like:

- Military readiness;

- Oil and gas activities;

- Other energy activities (renewable and LNG);

- Research other non-directed activities; and

- Construction activities.

- It does not apply to commercial fisheries, which is covered in another section.

A consultation under the MMPA evaluates the “specified activities” (specified by the applicant for the MMPA authorization) within a specified geographic region, and an authorization for “take” may be issued if it can be determined that the take will: Be of small numbers; Have no more than a negligible impact on those marine mammal species/stocks; and not have an unmitigable adverse impact on the availability of the species/stock for subsistence uses.

A Real World Example: Wind Farms and Right Whales

To see how this all comes together, consider the example of offshore wind farms: The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) is the lead Federal agency because they’re responsible for approving or rejecting the Construction and Operations Plans (COP) for these complex projects.

The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis) is protected by both the ESA and MMPA and critical habitat has been designated for this species along the East Coast of the United States. The North Atlantic Right Whale, and its critical habitat, may be affected by construction and operation of wind farms along the East Coast of the United States. BOEM’s approval of a COP for a wind farm has the potential to affect this ESA-listed species, so they are an “action agency” under the ESA, and must consult with NMFS to ensure that their action does not jeopardize the continued existence of the species and/or adversely modify its designated critical habitat.

Any authorization for take under the MMPA is granted to the entity responsible for the take, who is also responsible for any mitigation (including avoidance and minimization) and reporting requirements that are part of the authorization. Therefore, in this example the wind farm developer, not BOEM, is responsible for applying for incidental take authorization under the MMPA from NMFS (PR1), because their actions have the potential to take marine mammals.

When NMFS PR1 proposes to issue an incidental take authorization under the MMPA for ESA-listed marine mammal species, this also makes NMFS PR1 an “action agency” under the ESA because issuance of take under the MMPA may affect ESA-listed species. Therefore, PR1 must also consult with PR5 (or NMFS regional office, as appropriate) on its action under the ESA.

From the above example, you can see the ESA applies to all federal agencies, and does not exempt NMFS from the need to consult on its own actions that may affect species under its jurisdiction (often referred to as internal consultation).

This need to consult also applies when any other NOAA line offices have activities that may either result in take of marine mammals and/or have the potential to affect ESA-listed species or their designated critical habitat, such as OR&R’s response and restoration activities. Such consultation/coordination to conserve and manage coastal and marine ecosystems and resources is part of NOAA’s mission.

Dale Youngkin is a biologist with the HQ Office of Protected Species. He has worked for NOAA for seven years in two different divisions in the Office of Protected Resources, and has an interest in science communications and its importance for conservation.