This blog was originally published on Nov. 28, 2018.

Walking the busy streets of Manhattan, it’s easy to overlook the Hudson River as a living ecosystem, or think about its natural history. The Iroquois people native to the area called the Hudson Muh-he-kun-ne-tuk —"river that flows two ways" — a nod to the twice-daily pulse of the tides. Estuaries, where freshwater rivers meet the saltwater ocean, are some of the most productive, important, and impacted environments on the planet. The Hudson-Raritan Estuary exemplifies these contrasts.

The Hudson-Raritan Estuary is an interconnected and dynamic ecosystem of tidal rivers including the Hudson, Passaic, and Raritan; tidal straits such as the East River and Arthur Kill; and diverse bays such as Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge and Raritan Bay.

These waterways host one of the most urbanized regions in the world, including over 20 million people who live, work, and recreate here. Centuries of urbanization and industrialization resulted in habitat loss, poor water quality, reduced wildlife, contamination of fisheries, and limited public access.

However, due to a variety of pollution-reduction programs over the last several decades, the Hudson-Raritan Estuary has improved and is home to a great diversity of fish and wildlife. Over 200 species of fish are found in this estuary, which serves as a passageway for species migrating between rivers and the ocean.

Anadromous fish like American shad, striped bass, river herring, and the Atlantic sturgeon spend their lives in the ocean, but migrate to rivers to spawn in freshwater. American eels do the opposite, traveling from the estuary’s fresh waters to the ocean to spawn.

Marshy islands provide critical nesting habitat for numerous birds such as herons, and wetlands at the edge of the water are home to a great diversity of life such as crabs and mussels. Beneath the waves are the remnants of great oyster beds.

Marshy islands provide critical nesting habitat for numerous birds such as herons, and wetlands at the edge of the water are home to a great diversity of life such as crabs and mussels. Beneath the waves are the remnants of great oyster beds.

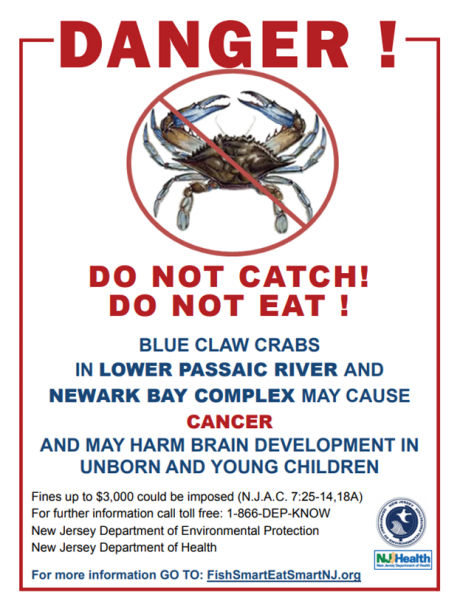

But while improvements in the estuary have been realized, much work remains. For example, toxic pollution from many historic hazardous waste sites continue to contaminate waterways, fish, and wildlife, resulting in numerous adverse impacts, including ongoing restrictions or bans on the consumption of some fish and shellfish.

To remedy this and other toxic impacts, NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration works on several large Superfund sites in the area including in the Hudson River, Passaic River, Berry’s Creek, Newtown Creek, and several more.

At these sites we work with our federal and state partners to recommend pollution control and cleanup strategies and develop and implement restoration projects, such as marsh creation and dam removals, to benefit fisheries, wildlife and the public.

Oil spills have also episodically closed waterways to commerce, fouled shorelines, oiled birds and other wildlife, and limited recreation. NOAA works with partners to prepare for spills, promptly respond when they occur, provide tools to predict where they’re going and their impacts, give expert guidance on cleanup, and develop and implement restoration projects.

The Hudson-Raritan River estuary is a place of contrasts — an important ecosystem, and a cultural and economic resource — on the doorstep of the biggest city in America. It’s a place where Wall Street and Atlantic sturgeon are next-door neighbors. It’s an ecosystem that has experienced enduring pollution, but where the efforts of NOAA and other federal, state, and local partners, communities, and industry are making a difference to cleanup and restore this amazing resource for the benefit of wildlife and people.

While there are signs of progress, of improvements in environmental quality, in fish and wildlife returning, there is still much work to be done. As the greater New York-New Jersey metropolitan area continues to thrive and evolve, the way NOAA studies and restores the Hudson-Raritan River Estuary will evolve also. By using sound science NOAA will continue to protect this unique waterway for the benefit of the millions of people who surround it.