As The Fog Cleared

The infamous fog of San Francisco was thick and gray the morning the Cosco Busan cargo ship crashed into the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. It was Nov. 7, 2007, and within seconds of the crash, 53,000 gallons of fuel oil were released into the surrounding waters. One of the largest oil spills in the history of the San Francisco Bay Area, it set into motion a series of events that ultimately led to a $44.4 million settlement with the companies responsible for the spill (Regal Stone Limited and Fleet Management Limited). $32.3 million of the settlement was earmarked for natural resource restoration projects managed by a trustee council with input from the public.

To the public, this has meant funding for bird, fish and habitat restoration work in the Bay and on outer coasts where impacts from the oil spill were felt. It has also been used to enhance shoreline parks and outdoor recreation in dozens of locations around the Bay Area, helping compensate the public for the lost visits to the beach when oil washed up on the shores.

That first morning in 2007, we didn’t really know how much oil had been spilled — initial reports indicated it was only a small amount. But as the fog lifted, it quickly became apparent that oil was spreading over a large expanse of the Bay. When I got the initial call about the spill, I had just landed in southern California to work on my major project at the time. My coworker on the phone suggested I get back to the Bay Area as soon as possible. For the next several weeks I worked long hours alongside fellow scientists to quickly organize and conduct the field work to evaluate natural resource damages from the Cosco Busan oil spill.

The type of oil that gushed into San Francisco Bay was bunker oil, which is commonly used to propel large ships and is different from crude oil or refined fuels. Bunker fuels are so viscous (thick and slow-moving) that they actually have to be heated to over 100 degrees Celsius (212 degrees Fahrenheit) in order to flow to ship engines.

As the thick bunker oil spread on the waters surrounding San Francisco, it turned into tarry patches and balls that eventually stranded along hundreds of miles of shoreline. Much of our understanding about the toxic effects from oil spills at that time had come from studies of spills of crude oil, such as the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska. But as we studied the effects of bunker oil on fish and wildlife after the Cosco Busan spill, we discovered bunker oil appeared to have different toxicological effects compared to crude oil.

Lingering Effects

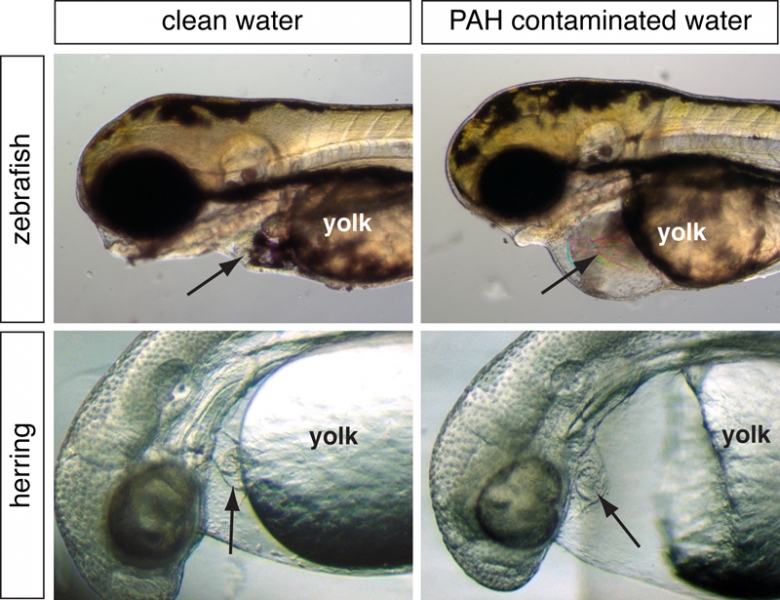

Two to three months after the spill, when the huge annual schools of Pacific herring entered San Francisco Bay to find their shallow spawning grounds, most of the shoreline and nearshore evidence of lingering bunker oil was already gone — either cleaned up, dissipated or at least hidden from view. But when we collected herring eggs from shallow areas both affected and unaffected by the spill, we made a remarkable discovery — almost all of the eggs collected from spill locations were dead or deformed. The eggs collected outside of the spill zone were largely normal. This was especially surprising given the lack of significant remaining evidence of bunker oil.

We conducted additional studies over two more seasons of herring spawning in the Bay and eventually concluded that the toxic characteristics of the bunker oil from the Cosco Busan spill affected as much as a quarter of the herring spawning in 2008. We also concluded that the effects didn’t carry over past that first spawning season after the spill. Our studies, directed by scientists from NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Bodega Marine Laboratory in California, forged new scientific understandings on the effects of oil spills on aquatic resources and have guided further progress on our assessment of present and future spills. In fact, the scientific studies of the effects of the 2007 Cosco Busan oil spill, particularly the magnification of oil toxicity caused by sunlight, set scientists on the path to further groundbreaking investigations during and after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. In the 10 years since the Cosco Busan spill, we have gained an even better understanding of the mechanisms by which oil exposures lead to cardiac deformities and other adverse effects in developing fish, and in other wildlife.

Next week will mark a full decade since the Cosco Busan oil spill. I’ve reflected on the countless hours of work that led to the settlement of damages: from the emergency responders cleaning up the oiled waters (and the thank-you cards to them from local school kids left on the beach) to the attorneys poring over the maritime and clean water laws violated by the spill. The 2012 settlement set us on the path toward the restoration of the impacts the spill had on San Francisco Bay and the people who recreate around the Bay.

The Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan for the Cosco Busan oil spill provides details on the restoration projects that have been and continue to be implemented; you can review it her

This blog post was written by Greg Baker. Baker works as an environmental scientist in the Assessment and Restoration Division of NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration and is based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

RESOURCES

To learn more about the Cosco Busan oil spill, you can also visit the resources below:

- Cosco Busan oil spill image gallery

- Making Waves podcast: episode 84 “Cosco Busan Settlement,” and episode 91, “Restoring San Francisco Bay.”

- Related articles:

- $36.8 Million Settlement to Restore Natural Resources and Improve Recreational Opportunities in Areas Affected by Cosco Busan Oil Spill Will Address Impacts from Ship that Struck the Bay Bridge

- $44 Million Natural Resource Damage Settlement to Restore San Francisco Bay After Cosco Busan Oil Spill

- DARRP Team Members Receive Award for Work on Cosco Busan Oil Spill Settlement

- Buoys Serve as Latest Gardening Tool for Restoring Eelgrass in San Francisco Bay

- California Department Fish and Wildlife

- Damage Assessment, Remediation, and Restoration Program Cosco Busan case page

- National Transportation Board accident report and presentation