On April 20, 2020, NOAA will join our state and federal partners in observing 10 years after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill — an incident that resulted in the tragic loss of human life and an unprecedented impact to the Gulf’s coastal resources and the people who depend on them. From March 30 to April 20, tune in as we go back in time to the day of our country’s largest marine oil spill, what’s happened since then, and how we’re better prepared for future spills. In this guest blog from our partners at the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium, learn more about oil spill science communicator Tara Skelton’s experiences as a resident of the Gulf of Mexico during Deepwater Horizon, and what she’s learned since then.

I was a freelance writer and mother of two living in coastal Mississippi when the Deepwater Horizon oil spill began in April of 2010. As boom went up around my local beaches and harbors, my concerns mirrored those I encountered in my community. Should I take my kids to the beach or out boating? Could we continue to safely buy our shrimp off the docks directly from local fishers? How long would all this last?

As tropical weather regulars, Gulf residents are no strangers to disaster. Hurricanes and other coastal storms blow through regularly, and then we all get together to work toward rebuilding. I wondered how long my little town and communities like ours around the Gulf would feel the effects of this disaster, one where you couldn’t immediately see what needed fixing. Because the Gulf is large and complex, scientists explained, answers could take a while and, in some cases, lead to more questions.

In 2016, I took a full-time position as the communicator for the Sea Grant Oil Spill Science Outreach Program. This team of science extension professionals works regionally with audiences just like me—people who rely on a healthy Gulf of Mexico for work or play—to share what researchers have discovered about the effects of Deepwater Horizon and other oil spills. We produce publications and sponsor seminars covering different aspects of oil spill science. I help my teammates translate technical research findings into language that anyone can understand. Not trained as a scientist myself, I joke that my expertise is much like an oil slick—wide but not very deep. That’s why when I want answers, I turn to the scientists I work with and the materials they’ve produced.

Here are some of the things I’ve learned since that April ten years ago:

-

It IS safe to eat Gulf seafood, swim and boat in our waters, and play on our beaches. To learn why, watch the short video "Ensuring the safety of seafood after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill" (below) or read the fact sheet "Is it safe? Examining health risks from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill" or longer outreach publications "The Deepwater Horizon oil spill’s impact on Gulf seafood" and "Navigating shifting sands: Oil on our beaches."

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/PLqFLXVUy3C14jDpgE0_PEeoGA_DZBdNzJ.jpg?itok=4rMTdMM1","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JX4M2EgPSfQ&list=PLqFLXVUy3C14jDpgE0_PEeoGA_DZBdNzJ&index=2&t=1s","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":1},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive, autoplaying)."]}

-

Good science takes time. Sometimes scientists’ understanding of a situation can evolve as more information becomes available. For that reason, my team updates and republishes our work if necessary, as we did with "Top 5 frequently asked questions about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill—Updated 2019."

-

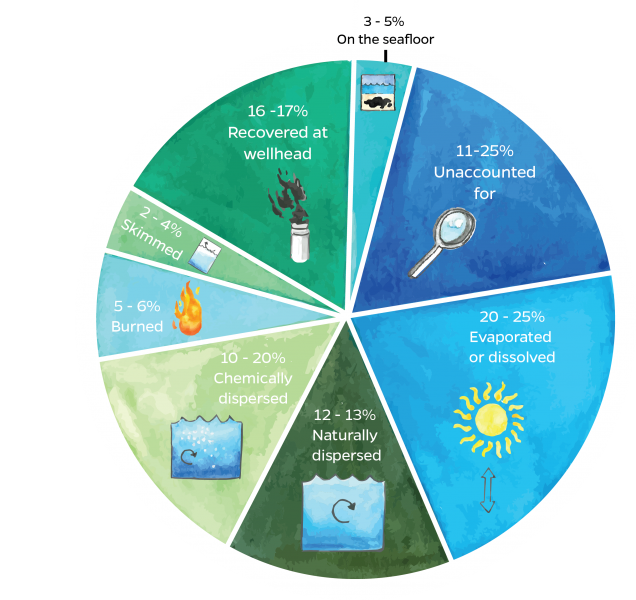

Scientists have a good idea of where in the Gulf ecosystem much of the Deepwater Horizon oil ended up, but that doesn’t mean they can account for every drop. Read "Where did the oil go? A Deepwater Horizon fact sheet," or for a more in-depth look, "Deepwater Horizon: Where did the oil go?"

This graphic from Deepwater Horizon: Where did the oil go? depicts estimates of where scientists think the Macondo oil wound up in the environment. Watercolors by Anna Hinkeldey. -

Results found in a lab are not always observed in the real world. For example, lab studies raised concerns that the dispersants responders used to keep oil from hitting shore might negatively impact marine life, but those concentrations were not found in coastal waters after Deepwater Horizon. My team produced a series of publications on the subject—"Chemical dispersants and their role in oil spill response;" "Responses of aquatic animals in the Gulf of Mexico to oil and dispersants;" and "Persistence, fate, and effectiveness of dispersants used during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill"—and a fact sheet—"Frequently asked questions: Dispersants edition"—that sums it up.

-

It wasn’t my imagination—people do respond differently to human-caused disasters like oil spills than to natural disasters. To learn more, check out the "The Deepwater Horizon oil spill’s impact on people’s health: Increases in stress and anxiety" and "Creating healthy communities to overcome oil spill disasters." The team also joined with the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to host a coast-to-coast workshop series on the oil spill disaster resilience. Reports and talks from the workshops can be found at Regional priority setting for health, social, and economic disruption from spills.

-

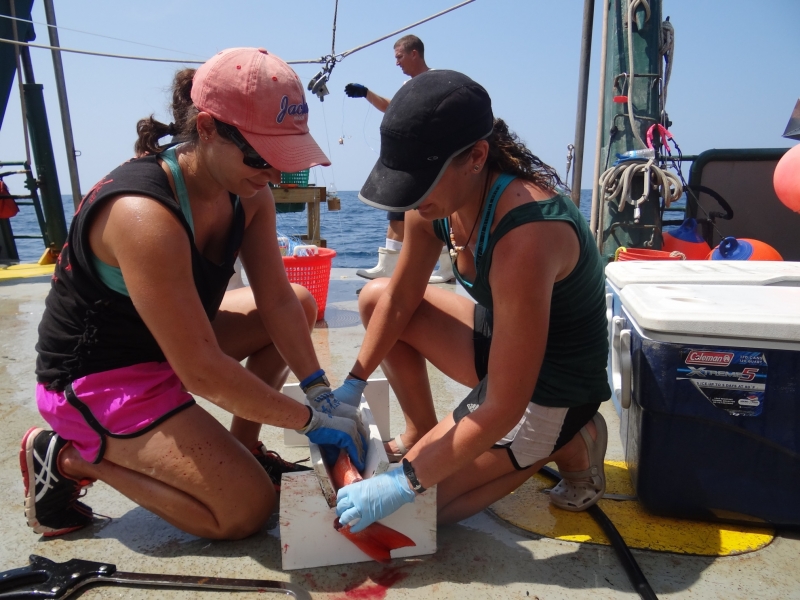

Part of the stress and anxiety humans face in the wake of an oil spill comes from damage to their livelihoods when fish populations are impacted or commercial fisheries closed. Watch a short video (below) showing how fishes’ bodies process oil or read more detail in "Fisheries landings and disasters in the Gulf of Mexico," "Impacts from the Deepwater Horizon to Gulf of Mexico fisheries," "Oysters and oil spills," and "Skin lesions in fish: Was there a connection to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill?"

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/f_-pmwMfW1I.jpg?itok=ynmuog2_","video_url":"https://youtu.be/f_-pmwMfW1I","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":1},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive, autoplaying)."]}

-

Even though the Deepwater Horizon oil spill negatively affected some marine animal populations, other factors in the highly complex Gulf of Mexico system frequently compounded adverse impacts. For example, cold-water stunning contributed to dolphin and turtle population declines in 2010: "Sea turtles and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill" and "The Deepwater Horizon oil spill’s impacts on bottlenose dolphins."

-

Scientists learned from Deepwater Horizon that even the smallest of neighbors in the water can make a big difference in overall outcomes or experience unexpected results. To learn more, read "Microbes and oil: What’s the connection?" or watch presentation videos from "Using the underdogs of the animal world to gain insights into impacts, recovery, and restoration after oil spills."

-

Oil spill response incorporates science, and it evolves as new tools become available. See the publication "Emerging surfactants, sorbents, and additives for use in oil spill clean-up" and presentation videos from the recent event "Herding oil at the surface: Surface collecting agents in oil spill response."

Oil coats this boat after a short trip off the coast of Dauphin Island, Alabama, in June 2010. Image credit: LaDon Swann. -

Speaking of technology, scientists have a suite of super-cool tools they use to study impacts. Check out the publications "Underwater vehicles used to study oil spills" and "In the air and on the water: Technology used to investigate oil spills" and presentation videos from "Technology & Deepwater Horizon" and "Technology used to study oil spills, Part 2" to learn more.

As oil exploration and transportation continues, so does the likelihood that another catastrophic spill could happen somewhere in the world. It is our hope that the library of publications and videos we’ve created will be a resource for anyone who finds themselves wondering what to expect when it takes place.

Tara Skelton is the Oil Spill Science Outreach Team Communicator for the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium. The four Gulf of Mexico Sea Grant College Programs with funding from partner Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative has assembled a team of oil spill science outreach specialists to collect and translate the latest peer-reviewed research for those who rely on a healthy marine ecosystem for work or recreation. To learn more about the team’s products and presentations, visit gulfseagrant.org/