This is the fourth in a 12-part monthly series profiling scientists and technicians who provide exemplary contributions to the mission of NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration (OR&R). This month’s profile is on environmental scientist Simeon Hahn.

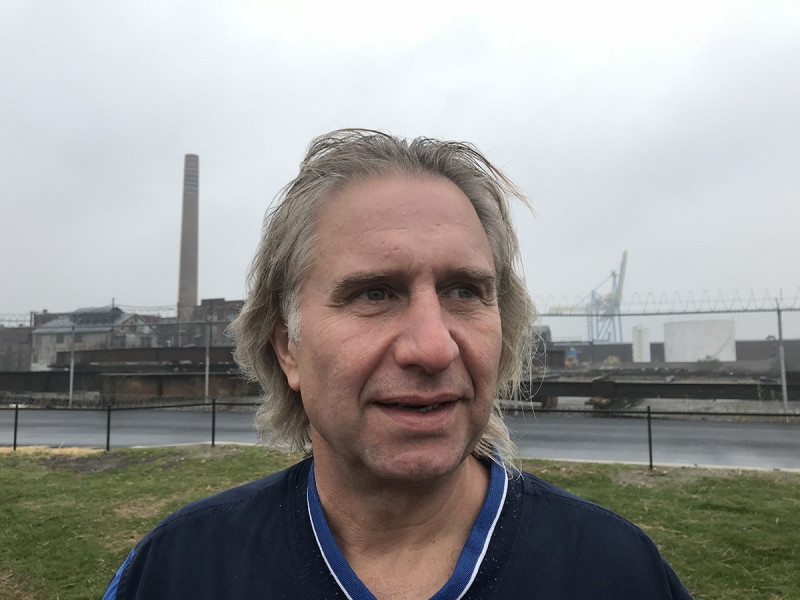

On a drizzly November day, I met Simeon Hahn at Phoenix Park in Camden, New Jersey to talk about his work. As a Philadelphia native, I wanted to learn more about the work NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration does in the area. It was also an opportunity for me to get to know Simeon, an environmental scientist and regional resource coordinator with OR&R.

Simeon grew up in the natural beauty of the Shenandoah Valley in Waynesboro, Virginia. His parents came from the Black Forest area in Germany, and later bought a cabin and land adjacent to the George Washington National Forest in Virginia.

The son of a research chemist, Simeon fondly remembers what it was like growing up under the tutelage of a strong academic who instilled education and science in him. Though where his father’s interests were more chemical, Simeon found his love for science in nature — captivated by the chance to step outside the lab and into the field.

Simeon received his bachelor’s degree in biology from James Madison University, and his master’s degree in entomology and applied ecology from the University of Delaware. After graduating, he worked for the U.S. Navy doing a wide variety of applied biology work and then transitioning into the Navy Superfund Program working in ecological risk assessment, site cleanups, and habitat restoration for almost 10 years.

Through his work with the Navy, Simeon met and worked with Ken Finkelstein, a former NOAA coastal resource coordinator who now works as a regional resource coordinator in Boston. It was from this connection that Simeon first heard of a position opening up for NOAA in the Environmental Protection Agency’s Mid-Atlantic region in Philadelphia.

That was nearly 20 years ago, and Simeon has been with NOAA ever since, working on sites such as Phoenix Park.

Phoenix Park sits at the edge of an industrial area along the Delaware River. It had at one point been a riverine habitat — though up until recently the area had been the site of an abandoned, contaminated industrial site, Simeon explained as he looked out at the park that has since taken its place.

Part of Simeon’s job has been to support the restoration of the site, which is now 6 acres of recreational green space, including winding paths and a boat launch. Further restoration is needed, and a significant shoreline restoration project is currently in the works.

Simeon co-chairs the Brownfields work group that led the Camden Phoenix Park project, along with co-chair Frank McLaughlin, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Brownfield section chief. He sites the project as one of the many successes to come out of the Urban Waters Federal

“My favorite part of my job is making relationships with my partners and especially the local communities and just seeing something like a contaminated site, like Phoenix Park, be redeveloped into a community asset,” Simeon said. “I'm especially satisfied when there is a strong habitat restoration and habitat component which allows for things like wildlife observations that kids in the community rarely, if ever, have seen.”

After looking at Phoenix Park, Simeon took me to look at another urban restoration project he has supported — a more than 60-acre site built on the Harrison Avenue Landfill, located at the confluence of the Cooper and Delaware Rivers. To convert the land into a park, the landfill was consolidated for stability, the shoreline was restored and stabilized, and a buried source of chemical contamination found in the landfill was remediated.

The project also led to the creation of a new community center — the recently developed Salvation Army Kroc Center — adjacent to the Cramer Hill neighborhood, which serves the community with recreational, educational, and family service facilities. In addition to the community center, local children will benefit from waterfront activities such as boating.

Simeon has a lot of enthusiasm about the potential of urban restoration and how community life can be enhanced by addressing the problems of industrial contamination. Working in urban areas allows Simeon the opportunity to do restoration work that focuses on the whole community and the human issues involved.

“We try to work with the community and others — regulators, officials, businesses, and such — to help redevelop sites, often riverfront sites, in a more holistic fashion, addressing community needs such as water quality, habitat, access and trails, economics, socio-economic issues, and more,” Simeon said. “... I try to bring more awareness, especially in urban water areas, to the full suite of services NOAA provides.”

Though he does a great deal of work in urban neighborhoods such as Camden, Simeon can also be deployed to a site following a spill.

During Deepwater Horizon, Simeon was asked to form and lead a workgroup to assess sea turtles and marine mammals — many of which were endangered species.

“The sea turtle marine mammal work was really rewarding in that there was not a lot of guidance on how to do these,” Simeon said. “I was able to meet and form a group of extremely talented NOAA people and other partners to initiate the assessment and ultimately the effort was quite successful.”

Outside of work, Simeon has a strong interest in sports. He grew up playing basketball and his daughter now plays for Villanova University. He remembers bringing her to the inner city of Wilmington at a young age. After she started playing, Simeon began coaching and mentoring in the inner city.

“It became clear to me real quick that most of these kids have been disconnected from their natural environment, which also was severely degraded by past industrialization and other issues like infrastructure and social issues,” he said.

Seeing an opportunity to raise awareness about the issue, Simeon collaborated with several basketball friends to start focusing on education, spiritual ecology, environmental justice awareness, and other topics. Simeon now gives presentations and leads field trips as part of this effort.

In addition to sports and environmental justice, Simeon also enjoys wildlife ecotourism, having visited Yellowstone and Glacier national parks, Alaska, and other popular wilderness destinations.

For Simeon, his interest in ecology runs deeper than just science. It’s also an area of spiritual connection for him.

“I went into ecology because I always had an interest and an admiration in the natural world for its beauty, but I also believe in a more connected universe and globe where humans are not necessarily at the top of the pyramid, like many religions present, but more an integral part with infinite connections,” he said.

To read more about Simeon and his work with Urban Waters Federal

Urban Waters Team Wins "People's Choice" Public Service Award

Renewal Ahead for Delaware River, Newest Site of Urban Waters Federal Partnership Program