When asked what oil looks like, most people would probably describe it similar to molasses — black, and somewhat viscous in appearance. But did you know, crude oils can come in a range of colors? From black to red to yellow, oil can appear in a number of different colors and consistencies. This can make it especially hard to find and identify oil from the air.

In the image above, a range of colors can be seen at the site of a well leak in Bayou Perot, Louisiana. The oil that is closest to the source — visibly spraying out of the well — is yellowish. As the oil collects in the pollution boom around it, it gets thicker and becomes orange. And the thickest oil, collected to the far end of the boom, is black.

While different types of oils can vary in appearance, oil slick appearance is also affected by weather conditions and how long the oil has been out on the water. Though images of a heavy continuous coating of oil on the sea or shoreline might be the first thing that comes to mind when you think of an oil spill, that same spill could look quite different after a few hours or days.

Over time, oil can become patchy, it can emulsify, or become mixed with water. The color and consistency can change as the oil encounters other materials in the water, or simply the exposure to air. Even close to the source of the spill the colors can be quite variable depending on the thickness of the oil.

During a spill response, trained aerial overflight experts serve as the eyes for the command post of spill responders. They report critical information like location, size, shape, color, and orientation of an oil slick.

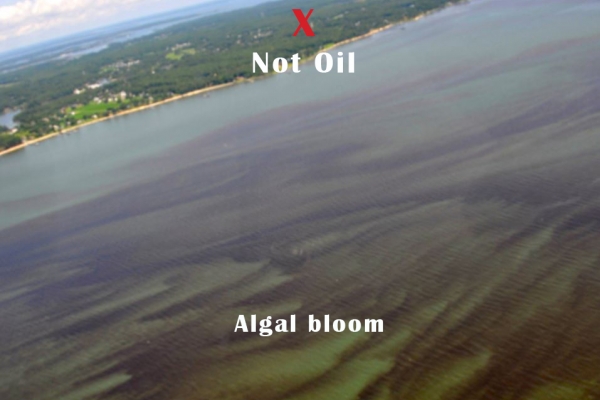

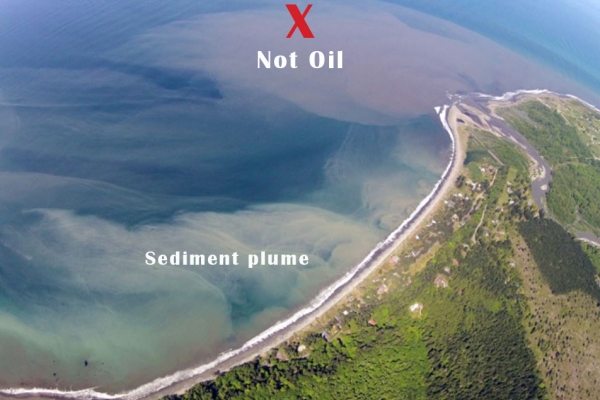

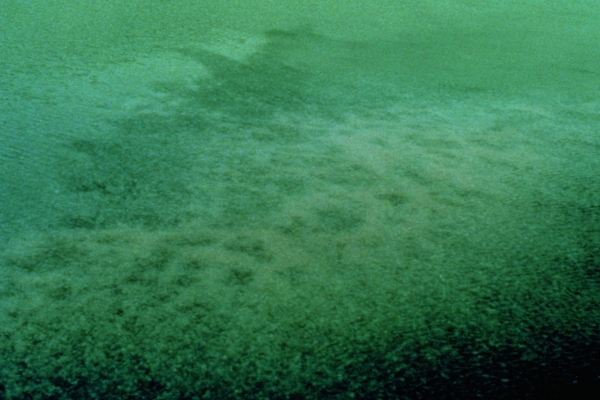

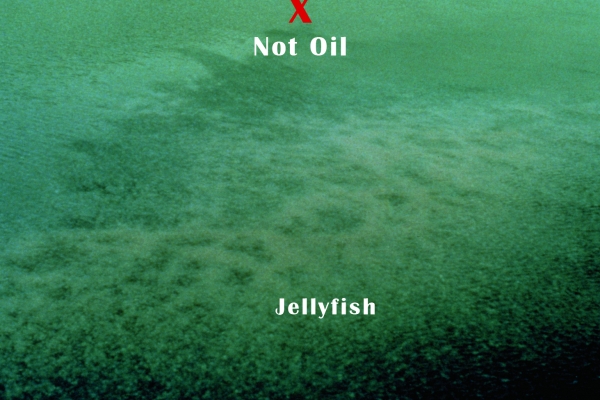

Because oil comes in such a wide variety of colors, it can easily be mistaken for something else — and vice versa. When searching by air, or even by satellite, responders can come across false positives for oil.

In this photo from a marina in Washington (right), this naturally occurring algae looks a lot like a reddish brown oil. When viewed from the air, algal blooms, boat wakes, seagrass, and many other things can look like oil. Important clues, such as if heavy pollen or algal blooms are common in the area, help aerial observers make the determination between false positives and the real deal. If the determination cannot be made by aerial observation, further investigation may be needed to properly identify the anomaly.

In the slideshow below, put your eyes, and your knowledge, to the test. Many of the images look very similar to oil — so much so that they required a second look to confirm their identity. Can you spot the false positives?

How did you do? Was there a particular false positive you struggled to identify? Share your thoughts and results in the comments below. You can also tweet us @NOAACleanCoasts or comment on Facebook @noaaresponserestoration.

To learn more and for training resources, visit the links below:

- Open Water Oil Identification Job Aid for Aerial Observation [PDF]

- Introduction to Observing Oil from Helicopters and Planes (online training: you’ll need to create a username and password).

- Oil Observation Checklist [PDF]

- OR&R Science of Oil Spills (SOS) classes include an overview of aerial observation during oil spill response. Learn more about SOS classes, and when and where the next class is scheduled.