With climate change comes an increased frequency in extreme weather events, such as hurricanes. NOAA monitors and predicts, responds to, and prepares for the impacts of climate change. In this blog, Charlie Henry, director of NOAA's Gulf of Mexico Disaster Response Center—the bedrock for OR&R's Disaster Preparedness Program—discusses the dangers of storm surge flooding.

A long time ago, I stood beside my grandfather outside of his house, looking toward the southeast at a very dark sky. We were 200 miles from where Hurricane Camille was making landfall in Mississippi—the second-most intense Atlantic tropical cyclone on record.

I was only 11-years-old at the time. They say children can sense when something is wrong and are often in tune with the worry and anxiety of those close to them. I remember that moment like it was yesterday—a still frame in my mind. My memories are much like that—a photo album of experiences represented as snapshots in my mind. My grandfather had experienced many hurricanes before and could guess as to the destruction occurring along the coast. I didn’t possess that experience, but I could sense his worry as we stood there together.

Months later, we visited the Mississippi coast, where we often vacationed. I remember seeing a shrimp boat the storm had carried across the highway. The hotel we usually stayed at was gone. There was nothing left but debris. What I saw that day as a young boy—a lot of which I didn’t fully understand—stayed with me for the rest of my life. How could a shrimp boat be carried across a highway? At the time, I didn’t know much about hurricanes or storm surge. I only knew that where I had spent past summer vacations was gone, and now, summers seemed to be forever changed.

The Power of Storm Surge

Hurricanes are rated on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. This ranks tropical cyclones by category, on a scale of 1 to 5, based primarily on wind speed. Hurricane-force winds can be very destructive. In a major Category 3 storm with sustained winds between 111 and 129 mph, well-built homes may incur significant damage; trees can snap or be uprooted, and water and electricity are typically unavailable for several days to weeks after the storm. During a Category 5 storm with winds exceeding 157 mph, catastrophic wind damage will occur. In modern times, only four storms have made landfall as a Category 5 event: Hurricane Michael in 2018, Hurricane Andrew in 1992, Hurricane Camille in 1969, and the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. To put things in perspective, Hurricane Katrina in 2005—known as the most costly hurricane on record in the U.S.—slammed Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and the Florida Panhandle as a Category 3 storm.

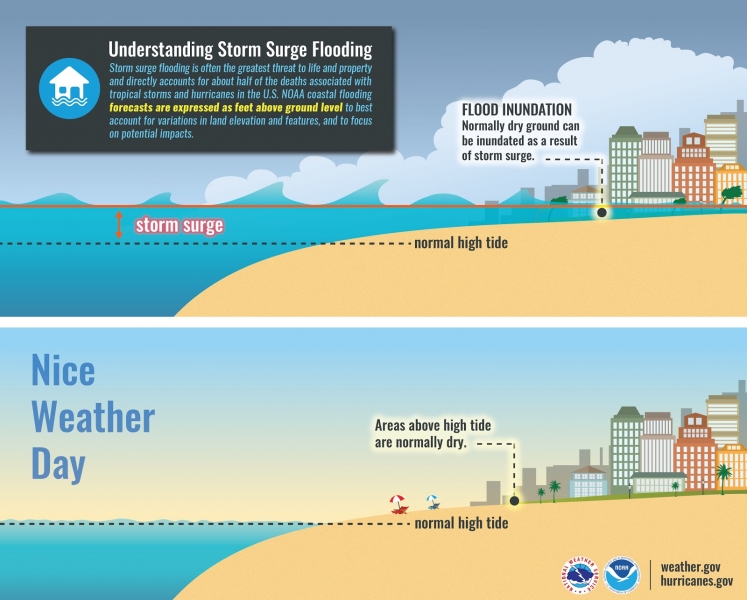

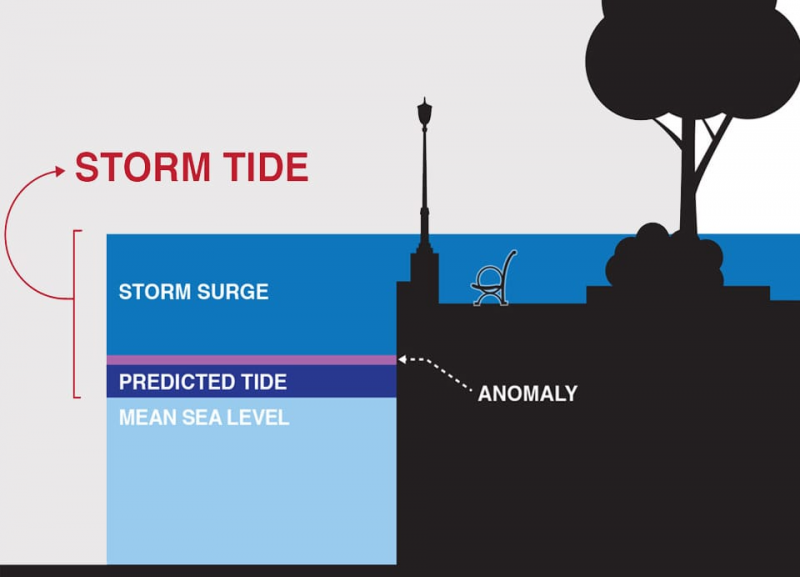

The winds from a hurricane can be devastating, yet for some hurricanes, the greatest threat is not the wind, but rather the water pushed by the wind as storm-surge and rain-induced inland flooding. Storm surge values do not correlate well to the hurricane categories of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale as they are based only on winds and do not account for storm surge.

According to NOAA’s National Weather Service, storm surge occurs when strong hurricane winds blow along the ocean surface and cause water to pile up as it approaches the shoreline. Low pressure at the storm's center causes water to bulge upward. Waves move on top of the surge and cause even more damage by acting as battering rams to infrastructure such as homes, businesses, and roads.

Remembering Hurricane Katrina’s Storm Surge Impacts

During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the storm surge was estimated between 25 to 28 feet above the normal tide and devastated portions of the northern Gulf of Mexico coast. In the small town of Pass Christian, Mississippi, the record U.S. storm surge height was documented at 27.8 feet. Both the direct and indirect impacts of the water did the greatest amount of damage and claimed the most lives during Hurricane Katrina.

When Hurricane Katrina made landfall on Aug. 29, 2005, I was a NOAA employee living in New Orleans. Part of my job responsibilities involved serving as a science advisor to the United States Coast Guard for oil and chemical spills and other threats to which the Coast Guard responds.

I know my memories of Hurricane Katrina are not unique. There were millions of people along the northern Gulf of Mexico, from Southeastern Louisiana to the Florida Panhandle, who experienced Hurricane Katrina up close and very personally. Some were even my relatives, friends, and colleagues. And some were NOAA employees, like me.

Hurricane Katrina was responsible for the death of nearly 2,000 people in Louisiana alone. Most of the fatalities in New Orleans and St. Bernard parish died in their residences—many of whom drowned in their attic. New Orleans mostly suffered from flooding as a result of failed levees caused by the storm surge directly and indirectly. South of New Orleans in Plaquemine Parish, where Hurricane Katrina first made landfall on the Northern Gulf of Mexico coast, houses were swept away and piled against levees as debris.

Once Katrina crossed over Plaquemine Parish, its eye was again over the Gulf of Mexico before it made a second devastating landfall on the Mississippi coast—this time sweeping away sections of bridges and everything else in its path. Ahead of the eye and stretching for hundreds of miles was the storm surge. Along the coast of Mississippi, a few homes and buildings were spared complete devastation. It’s hard to describe many of these mental images, but they are a stark reminder of the power of storm surge and the need to be prepared.

Be Prepared for Storm Surge Threats

Storm surge is often the greatest threat to life and property from a hurricane. It poses a significant risk for drowning and the destruction of infrastructure. It only takes six inches of fast-moving flood water to knock over an average-sized adult, and only two feet of rushing water to carry away most vehicles. As we enter the heart of the Atlantic Hurricane season, here are some steps to take to prepare for the dangers of storm surge:

- Find out if you live in a hurricane evacuation zone.

- Evacuate as instructed. Storm surge can cause water levels to rise quickly and flood large areas within mere minutes.

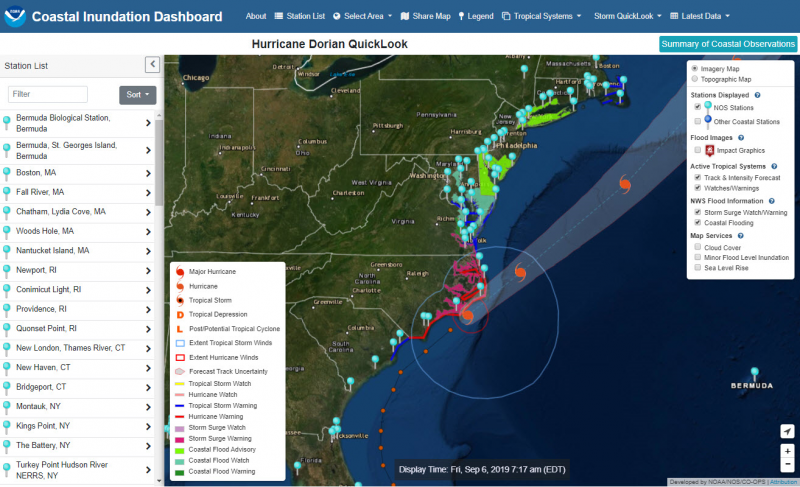

- If a hurricane is threatening your community, visit the National Hurricane Center website to view maps that show potential storm surge flooding for your area.

- The Potential Storm Surge Flooding Map is different from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood insurance rate maps and hurricane evacuation zone maps. You do not have to live in a floodplain to experience storm surge.

- Visit the National Ocean Service’s Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS) Coastal Inundation Dashboard to view real-time and historical coastal flood information at select locations.

Remember, storm surge can occur before, during, and even after the storm passes through an area. To learn more about hurricanes hazards, safety tips, and useful resources, visit NOAA’s National Weather Service and National Ocean Service websites.

As a young boy, I didn’t understand the worry and anxiety I sensed in my grandfather as we looked out toward the coast and devastation Hurricane Camille was causing. But after living along the Gulf Coast and through my career with NOAA, I have many personal memories and experiences that help put these storms into perspective. Whether you live along the Gulf Coast, another hurricane-prone coast, or somewhere else in the United States, please take my advice and understand the dangers of storm surge and flooding.