What do you do with excess beakers, boxes of test tubes, wind gauges, oceanographic buoys, and other science equipment that has been phased out of routine operations? In the spirit of reuse of viable material and the reduction of needless waste, you give it to other scientific organizations.

That’s what we are doing. In the past, we needed the lab and its equipment to conduct tests related to spill response and other environmental hazards. As new programs within NOAA and other organizations emerged, the need to collect our own environmental data and conduct lab work was distributed among those offices.

That left us with a lab we no longer needed, full of equipment no longer in use. The room quickly became more storage room than science lab, filled with items that were in excellent shape. Rather than let the equipment languish and continue gathering dust, we decided it was time to share. If you’re a government agency it gets tricky when you have equipment no longer in use but still useable. It can’t just be given away. There are rules that have to be followed before you can give away equipment to an organization outside your own.

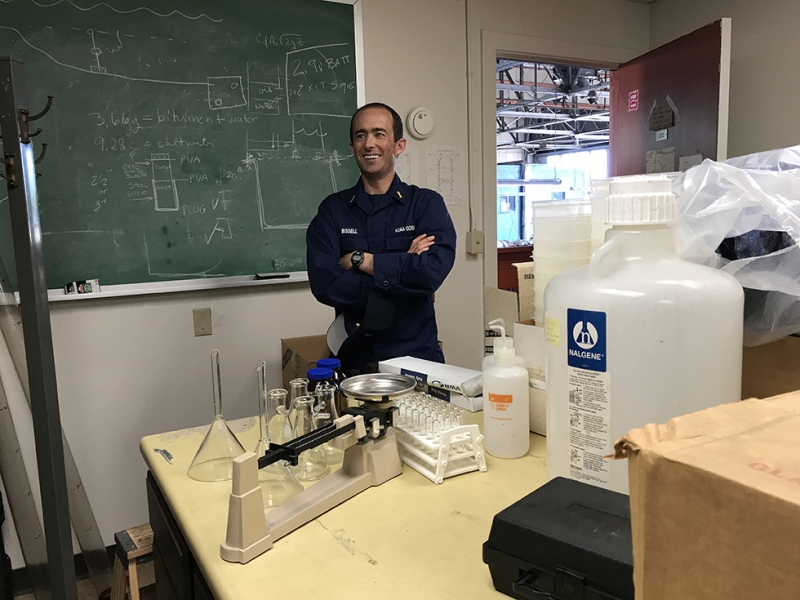

“My job was to find a home for everything that could still be used,” said Ensign Matthew Bissell, a regional response officer with the Emergency Response Division. “I started calling offices within NOAA and then the University of Washington.”

After his initial calls, Bissell said about half of the equipment was snapped up, particularly the larger pieces like oceanographic buoys, wind gauges, and water current meters.

The lab is behind a locked door inside one of the old aircraft hangars at NOAA’s Western Regional Center in Seattle, remainders from the campus’s former use as a naval air station. Despite the building’s size, work space is always in demand. The Seattle campus houses the largest variety of NOAA programs at a single location in the United States.

One of the challenges of the project was to figure out what some of the equipment was and determine if it was still operational. Then it was time to sort out what we may still need and what was excess.

“Some of the stacked boxes had not been opened in over twenty years,” Bissell said.“I felt like an archaeologist unearthing a new-found site.”

The task quickly turned into an exploration of how new technologies change the way we work. A case in point was the discovery of a 1979 Polaroid camera once used in a process to convert paper navigation charts into digital bathymetric files. These bathymetric files are vital for modeling ocean currents.

“At the time, this camera turned a 12-hour job into 2 hours of work – greatly increasing our response capabilities.This procedure has since been replaced by an even faster technology,” Bissell said.

Just because we no longer use the technology, didn’t mean someone else couldn’t put the working camera to use. Bissell found a home for the camera at the University of Washington’s School of Art and Design. It’s now used by a student focusing on antiquated photography techniques.

Now that many of the larger pieces have found new homes, our focus is on the smaller items like sample jars, flasks, scales, and other miscellaneous laboratory supplies. It’s expected to take about a year to complete the project. We are periodically holding “open houses” for other branches of NOAA to visit the lab and take what might be of use to them.

You can read more about how technology has changed our work in these articles:

- Meet the New CAMEO Chemicals Mobile App

- How NOAA Oil Spill Experts Got Involved With Chemical Spill Software

- From Paper to Pixels: Mapping Pollution Response in the Digital Age

- Latest NOAA Mapping Software Opens up New Possibilities for Emergency Responders

- For Oil and Chemical Spills, a New NOAA Tool to Help Predict Pollution’s Fate and Effects