It was a dark and stormy night.

It was dark, not because it was nighttime, but because sunlight cannot reach the deepest parts of the Gulf of Mexico. And it was stormy, not because of thunder and lighting, but from a toxic blizzard of oily marine snow that slowly entombed the depths.

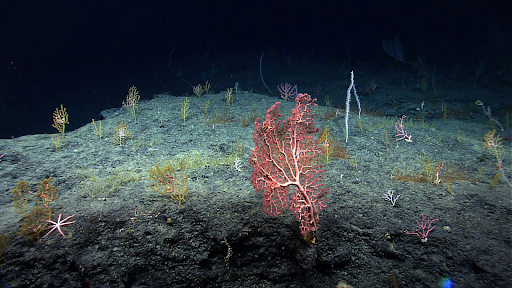

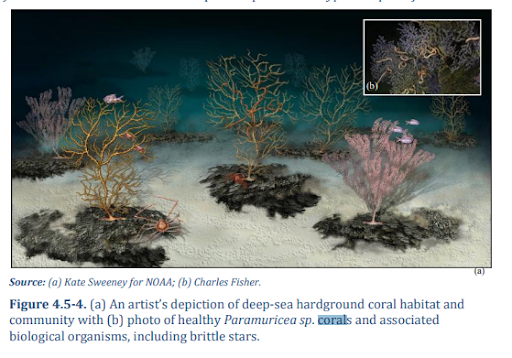

At the very bottom of the Gulf of Mexico live deep-sea corals—soft, alien versions of their more familiar shallow water cousins. For eons, deep-sea corals thrived in the depths, providing shelter for smaller denizens like brittlestars, sponges, and crabs. Until one day, dirty snow from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill descended upon them.

Oil stuck to particles in the water called marine snow. This oily snow sank through a mile of water onto the corals below. Like a poison rain, brown, clumpy droplets of oil fell thick on coral branches and the ocean floor. The snowfall may have lasted for months, but the impacts could last for years more.

Eleven years later, scientists are still working to discover how long the effects of this oily snow will last.

Oil in the Deep

On April 20, 2010, an explosion occurred on the Deepwater Horizon drilling platform in the Gulf of Mexico and started the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history. Scientists estimate that Deepwater Horizon oil covered over 400 square miles of deep-sea habitat. The impact of this pollution spanned even further.

Droplets of suspended oil formed a massive underwater plume, which was at times up to 650 feet thick and over a mile wide. This ghostly plume drifted more than 3,500 feet beneath the ocean surface, leaving a “bathtub ring” on bottom sediments wherever it went. In total, the plume covered more than 250 miles and lingered for more than five months after the spill ended.

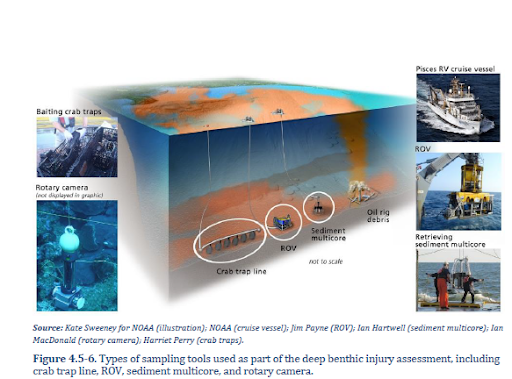

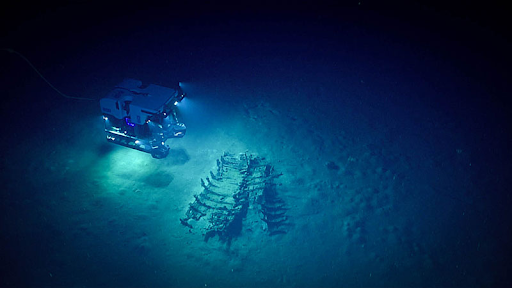

Scientists who work in deep-sea environments face many logistical challenges, including remote sites, darkness at depth, extreme cold, and limited time available for making observations. NOAA and our partners used specialized tools and techniques to overcome these challenges, including specialized equipment, such as autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), towed cameras, and remote coring devices.

Many coral colonies were observed as partly or entirely coated in a clumpy brown material called "floc." Chemical analysis of the floc revealed petroleum droplets that matched Deepwater Horizon oil’s chemical signature.

Impacts on Deep-Sea Corals

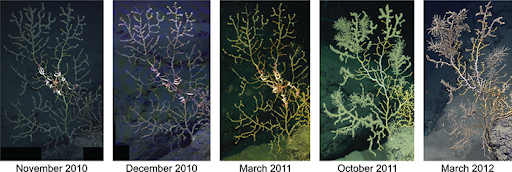

Of the seven deep sea coral sites nearest to the wellhead, four experienced some degree of injury attributed to the spill. In the weeks and years following the spill scientists observed corals that had been covered in floc retract their frilly tentacles from their branching arms. Mucus hung from the skeletons, and whole patches of dead tissue sloughed off.

Instead of brittlestars, fuzzy marine invertebrates called hydroids moved in on the damaged corals. In some cases entire colonies of coral were killed. These impacts were consistent with corals exposed to Deepwater Horizon oil in the lab, and were not observed in deep-sea coral colonies outside of the oil footprint, making scientists confident that the oil spill was to blame.

It has been eleven years since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. That seems like a long time for us, but it isn’t for deep-sea corals. Some of the corals injured during Deepwater Horizon were estimated to be more than 500 years old. These creatures grow and reproduce incredibly slowly, indicating that their recovery will also be slow. Scientists estimate that it will take between decades and centuries for deep-sea coral colonies to recover to a pre-Deepwater Horizon state, if they do at all.

The Truly Scary Part

The truly scary part of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill was how humans can impact the planet in ways we can’t predict or understand in advance.

The deep-sea floor covers over half of the earth’s surface and yet scientists arguably know less about the deep-sea floor than the surface of the moon. Even less is known about the deep water environment and these deep waters make up the largest habitat on the planet. For many areas in the northern Gulf of Mexico, there was also limited pre-spill data to compare this post-spill research to. Research during Deepwater Horizon and in the decade since has greatly advanced what scientists know about these habitats.

Emerging research suggests that deep-sea corals provide valuable, and possibly unique, ecosystem services for different species. For example, in the Northern Gulf of Mexico the goosefish is only found in deep-sea coral habitats. Redfish larvae use these corals as nursery habitat, and deep-sea octocorals can host the egg cases of cat sharks.

These are just several examples of potentially unique, but important roles that deep-sea habitats can play in supporting the larger marine ecosystem. The full extent to which Deepwater Horizon impacted species that utilize deep-sea coral habitats is still a mystery.

This Was a Spooky Science Story: Deep-Sea Corals Entombed by an Oily Snow

NOAA and our partners worked to understand the impacts of Deepwater Horizon, which resulted in a historic $8.8 Billion settlement to restore the Northern Gulf of Mexico. This work includes projects to understand and restore deep-sea habitats.

NOAA scientists continue to research deep-sea coral communities in the Gulf of Mexico and around the world. By working to understand deep-sea corals, we will be better able to conserve, protect and restore them.