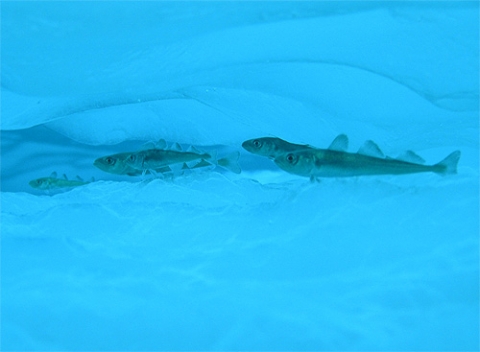

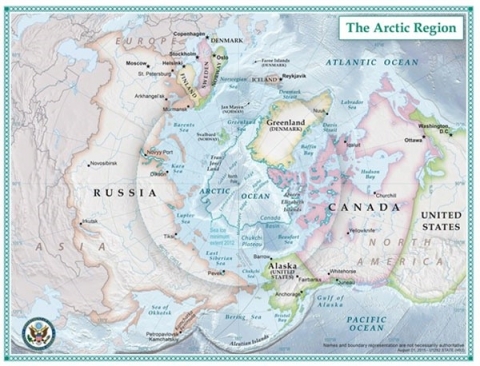

Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida) are small, ice-affiliated forage fish, that can make up more than 80% of all living fish in Arctic waters. Arctic cod have a circumpolar distribution that includes the Chukchi, Beaufort, and Bering seas in the Alaskan Arctic, and are a critical link in Arctic food webs.

These fish are one of the primary consumers of plankton that develop around sea ice and, in turn, are an important prey item for many marine mammals, birds, and fish. This keystone Arctic species is also particularly vulnerable to oil spills, which was the focus of a new study titled “Embryonic crude oil exposure impairs growth and lipid allocation in a keystone Arctic forage fish.”

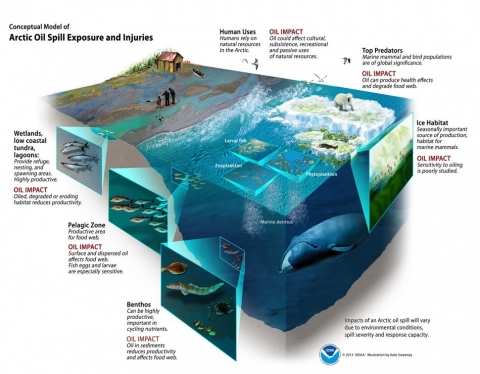

Developing Arctic cod eggs float near the surface of the water and they spend their early life stages underneath sea ice and along ice edges. These are the same places where oil would concentrate in the event of an oil spill, putting these growing fish in harm's way.

Vessel traffic and oil development have increased in the Arctic in response to warming oceans and declining sea ice. Anywhere oil is collected, transported, or refined there is a risk of oil spills. As ship traffic and oil development increase in the Arctic, the risk of oil spills also increases.

Given the importance of Arctic cod to their ecosystem, and their vulnerability to oil exposure, understanding the sensitivity of this species to oil is critical for evaluating risks. We need sound science to make decisions about emergency response during oil spills, and to assess injuries to natural resources afterward.

Imitating an Arctic Oil Spill

OR&R’s Assessment and Restoration Division teamed up with NOAA’s Alaska and Northwest Fisheries Science Centers, Oregon State University, SINTEF Ocean, and Norway’s Institute of Marine Research to implement multi-disciplinary laboratory studies of oil impacts on Arctic cod. The work was carried out at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center laboratory in Oregon, where a successful Arctic cod broodstock program has been established.

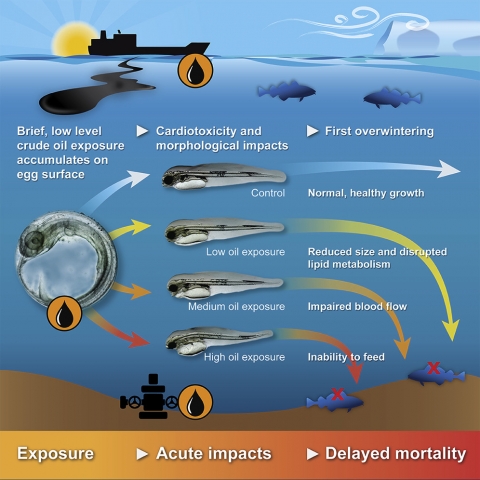

Arctic cod eggs were exposed to low concentrations of crude oil for three days in the middle of their 40-day embryonic (egg) development phase, simulating what might happen in the environment after a spill. The eggs collected droplets of oil on their shells and accumulated toxic chemicals in their bodies.

Following the oil exposure, the embryos were maintained in clean water until they hatched and developed into larvae. Some were raised until they developed into juveniles, about 200 days post-fertilization.

The oil exposure caused immediate toxic effects in embryos and early larvae. At the highest tested concentrations, some embryos died before they hatched, and those that survived were smaller at hatching, had misshapen jaws, or had malformed hearts with irregular heart rates.

Even fish that had been exposed to the lowest concentrations of oil and appeared to be normal larvae and juveniles showed critical delayed impacts. These exposed Arctic cod were 25-30% smaller than fish that had not been exposed to oil. Most importantly, the exposed fish were not able to effectively process and store fat.

Young Arctic cod must reach a certain size and have sufficient fat reserves in order to survive their first winter when prey are much less abundant. When competition and environmental conditions are tough, even small abnormalities can determine if Arctic cod survive their first winter.

Applying Sound Science to Prepare for Arctic Oil Spills

This research shows that Arctic cod are extremely sensitive to oil exposure. Even brief, low-concentration exposures lead to acute and delayed health impacts. Arctic cod that appear superficially unaffected can have growth and fat storage issues that reduce their survival later in life.

Understanding this species’ sensitivity and the potential for longer-term impacts from early life stage exposures is incredibly important. It allows scientists to accurately assess risks and impacts from oil spills, and prepare for future oil spill disasters in the Arctic.

These discoveries are among the first from NOAA’s ongoing work with Arctic cod. Our research is providing new insights into how toxic effects from early life-stage exposure can reduce fish survival later in life, and expanding our knowledge of sensitive Arctic species and habitats.

In science, each answer brings more questions. The research team is developing tools and methods for evaluating the toxic effects measured in laboratory studies in the field after a spill. Related investigations are examining how warmer temperatures, ocean acidification, and ultraviolet exposure intensify the impacts of oil spills. As the Arctic becomes warmer and human activities become more frequent, these studies could shed light on how oil spills could impact Arctic cod populations and the marine communities that they support.

These advancements in sound science support OR&R’s efforts to prepare for oil spill response, injury assessment, and restoration in the Alaskan Arctic.